THE TRUTH IS ALWAYS ON THE OTHER SIDE

Who Wants to Be a Slave? The Technocratic Convergence of Humans and Data

Although these two gentlemen did not yet know in 2020 that the so-called “pandemic” was and still is a highly criminal lie, manipulation and fraud to harm and kill people, to endlave them and bring them under absolute control(the criminal new UN-treaty and also thhe criminal new WHO-treaty!!) they have both written a really excellent and very efficiently researched article that one should definitely read!!!

https://www.frontiersin.org/journals/communication/articles/10.3389/fcomm.2020.00037/full

Man is born free but everywhere he is in chains.

—Jean-Jacques Rousseau

Introduction

“We shape our tools and, thereafter, our tools shape us.” This aphorism, attributed often to media scholar Marshall McLuhan, comes from John Culkin, a friend of McLuhan's who reflects on the theorist's ideas and how they might serve the classroom teacher contending with the demands and distractions characteristic of the so-called “new electronic environment” (Culkin, 1967, p. 53). It is, as of this writing, a 50-years-old insight that might be one of the most prescient today. Culkin's article distills McLuhan's major thoughts on technology, their omnipresence and power to serve as the primary instruments by which public perceptions of the empirical world are mediated, manipulated, and managed.

The main title of this essay is a simple question for readers to ponder how, in this period of the Information Age, media technologies give shape to the “mind-forged manacles” (Blake, 1794) that influence behavior (Packard, 1957/2007, p. 32) and shape perception about the degradation of human sovereignty, agency, and privacy. In light of these powerful tools of information processing and dissemination, our central purpose is to critically examine how certain media tools and content normalize the dispossession of basic human and civil rights and work to prepare people mentally for unquestioning service as cogs in the global capitalist machinery.

In a world where political institutions profess to serve the public interest and yet demonstrate scarcely the will or know-how to restrain the self-interested greed of transnational corporations (Sachs, 2019), we explore how organizations, platforms, and content serve “the power elite”1 (Mills, 1956, p. 73). Discussion begins from the premise that the dominant mainstream media in contemporary life remain as the prime movers of mass persuasion steering citizens toward obedient self-sacrifice to the prevailing neoliberal order.

Whereas Herman and Chomsky observed of traditional media that their “function is to amuse, entertain, inform, and inculcate individuals with [acceptable] values, beliefs, and codes of behavior” (Herman and Chomsky, 1988, p. 1), we suggest that emerging technologies not only “integrate [people] into the institutional structures of the larger society” (p. 1), but also into the so-called free market. We analyze the persuasive communications that serve this emerging order of the market working to integrate human beings into the forthcoming Internet of Things (IoT) where all organic and inorganic objects are prepared for sale and purchase2.

A Brief History of Convergence

This position begs the question: How could technology and media wield such degrees of control over people? Greater awareness of their hidden hegemonic power begins, we argue, with an acknowledgment of their unassuming influence over human perception (Bernays, 1928/2005, p. 47; Packard, 1957/2007, p. 144). Recent history provides a window through which to see these “known unknowns”3 which, too often, escape the critical awareness of the masses.

During the emergence of the electronic age, McLuhan noticed those around him consistently failing to recognize the influence that technologies had on human thought and behavior as his contemporaries interpreted their deeper meanings in terms of the past—as though they were seeing the present as an image in a rearview mirror. In 1969, he noted that, “Today we live invested with an electronic information environment that is quite as imperceptible to us as water to a fish” (McLuhan, 1969, p. 5).

In contemporary post-industrial life, however, the sheer inescapability of this environment and its influence on the public mind is deceiving. Both the natural and conditioned environments of our dwellings and public spaces, awash with waves of radiation imperceptible to the eye, bear the signals our bodies absorb and minds decode (Broudy et al., 2020). Only the absence of this packet-saturated air apprises us, like fish without water, of the kind of oxygen we are conditioned to believe we need. The ten-second delay for a personal device to reconnect to a WiFi may feel like drowning for those who demand “instant, or near real-time, access to alternate social worlds” (Tanji and Broudy, 2017, p. 209).

So it is that we muse about how far we have progressed from the days of the printing press; the Internet has empowered us each to communicate to the masses! The ubiquitous Internet (Rectenwald, 2019, p. 31)—the countless switches, servers, and meters of fiberoptic cable through which meaning moves globally—evokes an attractive illusion. That is, common citizens hold ample communicative power and autonomy to precipitate positive social change. Such is the utopian view of a social world cultivated by convenient collaborations with others across national boundaries and digital platforms freed, we hastily suppose, from state constraints and corporate influences. This idealized perception, however, is presently being undermined through a kind of convergence managed by elite corporate power, “a happy few who own and run the handful of corporations that dominate” (Bergman, 2018, p. 160).

Henry Jenkins observed in 2006 that, “Digitization set the conditions for convergence” while “corporate conglomerates created its imperative” (p. 11). AT&T's (telecommunications) June 2018 acquisition of Time Warner (media and networks) illustrates the kind of conglomeration Jenkins had called attention to. He described this process as “both top-down corporate-driven … and bottom-up consumer-driven ….” (2006, p. 18). The optimism expressed by Jenkins, however, that convergence is also consumer-driven, might appear somewhat myopic today with the top-down encroachments of Artificial Intelligence (AI) into every facet of public, private, and professional life.

From the perspective of the common citizen, the struggle today to locate in mainstream media some clarity and truth about the objective world and its existential threats to society can arouse our attention to the once-imperceptible.

Sometimes, corporate and grassroots convergence reinforce each other, creating closer, more rewarding relations between media producers and consumers (Jenkins, 2006, p. 18).

While citizens have long cherished their rights to participate in democratic processes and to exercise their civil rights, they have also been increasingly besieged by the centralizing forces of the State allied with corporate power. With “The Corporate Takeover of Democracy” (Chomsky, 2010) cemented in 2010, scholars have devoted entire volumes to its usurpation. Mark Crispin Miller, for example, writes about “the displacement of paper ballots, hand-counted in the open, by electronic voting systems owned and run by private companies” (Miller, personal communication). In the wake of 9/11, the power elites have steadily tightened control over press freedoms and free speech on digital platforms in accordance with the oppressive mandates of the USA PATRIOT ACT and, as presently witnessed, the so-called “COVID-19” plandemic. Corporate and state power converge, here, to control public perception. In the United States, for example, a study by Gilens and Page concludes that the wishes of the people have “a non-significant [or] near-zero level” (Gilens and Page, 2014) impact on the creation of laws that improve policies for the public good.

Hardly surprising are the reasons why citizens are increasingly cynical, disengaged, and suspicious of the present political system largely captured by corporate power: their distrust is confirmed by both stolen democracy (Miller, 2000, 2004, 2017) and the long absence of social progress and upward mobility. The results of the Princeton study verify what had also been astutely described by analysts with CitiGroup in a 2005 shareholders prospectus leaked to the public. Ajay Kapur et al. had observed in a subsection titled, “Welcome to the Plutonomy Machine,” that the US, UK, and Canada are plutonomies governed by a “Managerial Technocratic Aristocracy” (Kapur et al., 2005).

The authors discuss the primary economic drivers of the plutonomy and offer instructive explanations for effectively increasing investment, consolidating power, and concentrating material wealth, “exploited best by the rich and educated” (Kapur et al., 2005). None of the features characteristic of typical egalitarian values, however, appear in the perspectives of the power elite: “Disruptive technology-driven productivity gains, creative financial innovation4, capitalist-friendly cooperative governments5, an international dimension of immigrants and overseas conquests invigorating wealth creation, the rule of law, and patenting inventions” (Kapur et al., 2005). While each aspect of the so-called plutonomy deserves its own analysis, only those most relevant to our aim find elaboration in the following sections6.

Perception and Awareness in the Hands of Technocrats

How is it that humans would permit their tools to surpass the value of humanity itself? Jacques Ellul described integration propaganda as an effort to adjust the public to desired patterns of thought and behavior which is focused on achieving full conformity (Ellul, 1965/1973, p. 71).

Surely, the invisible hand of the market and the effects of its magical tools on governance have remained mostly hidden from public view. As McLuhan had postulated in the 1960s, if the “growing electronic environment” was the global village whose members largely operated without the constraints of space and time, then the Internet has become its central nervous system.

Has the technocracy effectively assimilated democracy? Chris Smith observes that Neuralink, a company founded by Elon Musk, “already has chips and a way of connecting to the brain and a computer” (Smith, 2019). Today, the Internet threatens to fully integrate people into a seamless neural matrix enhanced by the tools of an augmented (or enhanced) reality. At the 2017 World Government Forum in Dubai, for example, Musk referred to the gaming industry as a future model of social organization.

Games will be indistinguishable from reality; they will be so realistic, you will not be able to tell the difference between the game and reality as we know it, [which begs the question], how do we know that this didn't happen in the past and we are not in one of those games ourselves? (Musk, 2017).

Empowered to develop another level of perceived objective reality, the programmer, thus, becomes the (re)creator of a new form of social life devoid of the necessity of politics. Herbert Schiller warned of the power of the “informational infrastructure,” as he called it, where people absorb images and messages of the prevailing social order, which “create their frames of reference and perception,” and “insulate most from ever imagining an alternative social reality” (Schiller, 1999, 2000). This layer of convergence, widely understood as self-evident technological progress, foretells a future for human autonomy and sovereignty that hardly seems hopeful or chosen, bottom-up, by the masses.

Such moves are, also, unsurprising to the keen observer. In reflecting on C. Wright Mills' 1956 conception of the power elite, Alan Wolfe notes that “America… had reached a point in which grand passions over ideas were exhausted. From now on, we would require technical expertise to solve our problems, not the musings of intellectuals” (Wolfe, 2001).

These new electronic tools and their growing pervasiveness, controlled by elite gatekeepers, and their importance to the reproduction of life portend a time when marketization and “the migration of everydayness as commercialization strategy” (Zuboff, 2015, p. 76) will likely erase the need not just for political discourse but, ultimately, its institutions. A growing fundamentalist faith in science and its technological offspring in the free market as mechanisms for solving social problems threaten political discourse seeking positive change.

In a 2009 interview with CNBC, Google Chairperson Eric Schmidt reveals another layer of convergence directed from the top-down, that of the tool itself as an agent of social change. Responding to criticism about Google's practices in marketizing its users' data, Schmidt observed

If you have something that you don't want anyone to know, maybe you shouldn't be doing it in the first place, but if you really need that kind of privacy, the reality is that search engines including Google do retain this information for some time, and it's important, for example that we are all subject in the United States to the Patriot Act. It is possible that that information could be made available to the authorities (Schmidt, 2009).

Here, Schmidt personifies data derived from search engines and, thereby, conjures the attractive illusion that big tech and its tools have emerged as new and unquestionable agents of state authority. With the marginalization of citizen voices—especially of dissident views since 9/11—genuine political discourse has been co-opted by these corporate mythologies and algorithms conditioning the masses that the neoliberal global order, managed by the technocracy, is not just advantageous but necessary. The implied message is sufficiently clear: resistance to social change engineered and enforced by these new tools is futile.

Human Beings to Hyper-Beings

In further highlighting a problem that our increasingly sophisticated tools present to us mere mortals, Musk's presentation illustrates yet another dimension of convergence. The entrepreneur himself became the medium through which the startling message arrived in the public discourse: since our communication tools are fast becoming too powerful for us humans to contain, we must merge with them. Is society itself no more than economy?

If humans want to continue to add value to the economy, they must augment their capabilities through a merger of biological intelligence and machine intelligence. If we fail to do this, we'll risk becoming ‘house cats’ to artificial intelligence (Musk, 2017).

Olivia Solon's response is to question whether Musk is right about the claimed necessity of becoming a cyborg (Solon, 2017). Again we see the personification of tools elevating inanimate created things to the stature of autonomous and sovereign agents as the intrinsic value of people is reduced to their data (Hirsch, 2013). Imbued with agency, tools assume a social position as natural extensions of the power elite, like little brothers to their Big Brother (Klaehn et al., 2018, p. 182) Such are the characterizations of tools born of the power of the technocrats who see in “disruptive technology-driven productivity gains” even greater opportunities for the capture and control of human resources. Zuboff, summarizes the problem with ironic pith.

Once we searched Google, but now Google searches us. Once we thought of digital services as free, but now surveillance capitalists think of us as free (Zuboff, 2019a,b).

Paradigm shifts in societies over history, however, appear as little surprise to careful observers. In 1980, Bertram Gross predicted, for example, the convergence of mass consumption and the corporate capture of the masses with the emergence of new information technologies. “The collection of information is now possible through increasingly sophisticated systems,” he notes, “including the more ominous forms of remote electronic surveillance” (1980, p. 49). Katherine Albrecht and Liz McIntyre describe this level of convergence in electronic surveillance as an industry that “has patented some fantastically sinister, sci-fi style business notions” (Albrecht and McIntyre, 2005, p. 4).

With ongoing advances in processing speed and networked computing, Gross notes, that “most disturbingly, the means of control over this great mass has been developed to such a degree that centralized systems can keep tabs on incredible amounts of information over long sequences of widely dispersed and decentralized activities” (1980, p. 49). In seeing the dazzling advances in tool-making, why do we fail to see further how these new tools will fundamentally alter the future?

“Pandemic” Neoliberalism

New tools beget new opportunities to enjoin the masses to today's neoliberal project. If we come to believe, as we are so conditioned by culture, education, and media, that time is money, it is reasonable to conclude that only the efficient use of time to pursue and amass money will become what we perceive to be central to our principal purpose as humans. The integration propaganda works to construct a self-fulfilling prophecy: new tools and practices in efficiency, introduced to the transaction, create positive feedback loops in a system that naturally increasingly needs and expects higher levels of efficiency. Hence, today's propaganda that signals the virtues of frictionless business transactions at points of sale that, in turn, further degrade social intercourse that could develop and potentially disrupt the system, its tools and practices.

A consistent campaigner for free market capitalism unfettered by regulatory safeguards, Rush Limbaugh observed, for example, that McDonald's had finally fixed its sinking stock value since it “replaced 2,500 human beings with digital kiosks” (Limbaugh, 2017). Yet again, with unpredictable human beings at least partly removed from the business transaction and replaced by shiny and efficient new kiosks, we see the convergence of how man and machine (or machined tools) have shaped and silenced us.

In such a social world, efficient tools shape perception that help “turn efficiency into a nearly universal desire” (Ritzer, 1993, p. 35). The system, thus, treats efficiency as a presupposed universal value, but George Woodcock reminds us in his timeless essay, “The Tyranny of the Clock,” that, “Complete liberty implies freedom from the tyranny of abstractions as well as from the rule of men” (Woodcock, 1944/1998, p. 301). While Limbaugh has long continued the tradition of claiming for the present system an unquestionable elegance, he was also speaking in code for the new liberalism that Wendy Brown had deconstructed in her book Undoing the Demos: Neoliberalism's Stealth Revolution (2015). Neoliberalism, Brown observes,

disseminates the model of the market to all domains and activities—even where money is not an issue—and configures human beings exhaustively as market actors, always, only, and everywhere as homo economicus (Brown, 2015, p. 31).

Such automated gains in business efficiency have been so significant that they silence even the political class. Daniel Fusfeld observed that, “As long as an economic system provides an acceptable degree of security, growing material wealth, and opportunity for further increase for the next generation, the average American does not ask who is running things or what goals are being pursued” (Fusfeld, 1989, p. 172). The tools of automation have become so efficient that they are replacing not just people in lines of traditional work, but threatening to dispossess the masses from resisting their own planned marginalization and obsolescence.

As regards the necessity of preserving this system, Silvia Federici notes that capitalism, through increasing privatization, must capture latent control of the means of production, which is fundamental to the reproduction of our lives—the land, the forest, the waters:

The process of dispossession has continued today to accelerate and… proceeds at a pace that is devastating, and it is… one of the main struggles on the planet, particularly in the so-called free world…. When you dispossess people of their means of reproduction, you are also dispossessing them from the knowledge they accumulate in their cultivation of the land. This also dispossesses people of their political… capacity of self-government,… community solidarity and decision-making (Federici, 2017).

Henry Giroux refers to this rationale of perpetual sacrifice as a “disposability machine” that is “relentlessly engaged in the production of an unchecked notion of individualism that both dissolves social bonds and removes any viable notion of agency from the landscape of social responsibility and ethical considerations” (Giroux, 2014). The ideology disposes of traditional ideas of and values in a cohesive society and, as consequence, divides and conquers the people—splintering citizens into competing tribes of market actors whose means of engaging with the socioeconomic landscape diverge widely.

The ideology helps further dispose of the value of human emotion (only insofar as emotions can be manipulated in the interest of increasing the consumption of products and acceptable ideas) (Packard, 1957/2007, p. 32; Bergman, 2018, p. 161). It sees citizens as hyper-rational predators roaming the free market single-mindedly focused on attending to primal urges. The neoliberal project is the dog-eat-dog world of social Darwinism where only the physically fittest, with minds molded to act instinctually to buy and sell, will survive the future global market, which will subsume the purpose and meaning of a civil society whose members abide in a shared sense of value in the commons and the common good. Pierre Bourdieu pointed early on to the causes and effects of this project

The movement toward the neoliberal utopia of a pure and perfect market is made possible by the politics of financial deregulation. (…) in… the nation whose space to maneuver continually decreases. In this way, a Darwinian world emerges—it is the struggle of all against all at all levels of the hierarchy, which finds support through everyone clinging to their job and organization under conditions of insecurity, suffering, and stress (Bourdieu, 1998).

Two decades since Bourdieu's description of the hoped-for neoliberal utopia, we can also see how the ideology of Social Justice has played a key part in erasing social bonds as social media tools ironically serve as platforms for further tribalizing the body politic (Kramer et al., 2014). Beyond battling everybody in a “war of all against all,” the body politic, observes Miller, has been effectively dismembered,

—society balkanized by race-and-gender, as well as ‘blue’ and ‘red’, so that the necessary solidarity of the have-nots has come to seem impossible. While this development was hastened, if not initiated, by the CIA from the late'60s, it's now been universalized by social media, which offers the illusory solace of a fierce sense of belonging, and enables each of us to vent ferociously against ‘Trump’, ‘Putin’, ‘Killary’, the ‘fascists’, ‘homophobes’, ‘anti-vaxxers’, ‘anti-semites’ or whatever other tribe we have to hate. Thus, Social Media transforms each one of us into prolific war-propagandists; and now that we're all ‘sheltering in place’, most of us have little else to do except flip out on Facebook, Twitter, Instagram, 24/7 (Miller, personal communication).

This system, managed by a technocratic elite, will remain unchallenged so long as the promise of material wealth can be sustained.

Bertram Gross foresaw in this emerging order a friendly sort of fascism in which, “more concentrated, unscrupulous, repressive, and militaristic control by a Big Business-Big Government partnership [aims] to preserve the privileges of the ultra-rich, the corporate overseers, and the brass in the military and civilian order” (1980, p. 167). He points out that this redesign of the social world is framed in public discourse as exceedingly “reasonable” and inexorable because it is overtly friendly—to business—and, thus, part and parcel of the logic of an efficient and free market. The problem for citizens who seek to preserve agency, autonomy, and sovereignty is first taking notice of how, with a wink and a smile, convergence also threatens basic rights through the guise of business as usual. Since 9/11, business as usual has been fully focused on reinforcing the claimed preeminence of safety and security as asserted by the “Big Business-Big Government partnership [among]… the ultra-rich, the corporate overseers, and the brass in the military and civilian order” (Gross, 1980, p. 167).

Speed and Safety: It's for Your Own Good

“Mankind barely noticed,” observed Edwin Black, “when the concept of massively organized information quietly emerged to become a means of social control, a weapon of war, and a roadmap for group destruction” (Black, 2001, p. 7). The question is, of what significance are the tools of this present period of the Information Age to the new socioeconomic order? The tools are at the very center of a nascent system of global slavery, its contours slightly blurred by the enticing integration propaganda, the imagery and language typical of advancing technological progress. Excitement generated by sophistication, speed, and efficiency mask the news of impending widespread captivity.

Modern history provides precedent and context. Black identifies the computer we had given shape to as the key tool that came, in time, to re-shape us. Without the computer in its infancy, leaders of the Nazi Party could not have organized and carried out their plans of identifying the undesirables, expelling them from society, confiscating their assets; sending them to ghettos; deporting them; and, finally, undertaking the efforts to exterminate them (Black, 2012).

With the assistance of IBM's Hollerith machine (a primitive precursor beside today's microprocessor), the Third Reich could store information on any process, individual, or location by the ingenuity of holes punched on paper cards in columns and rows. The Information Age, born not in Silicon Valley but in 1933 Berlin, individualizes statistical information. “Not only can I count you as a member of the crowd,” notes Black, “but I can individualize the information I have about you” (2012)—where you live, what your profession is, and where your bank accounts are.

Perhaps the greatest achievement of encoding paper cards with ethnographic data appeared in its concrete manifestation of tattoos emblazoned on the forearms of concentration camp prisoners. The numbered marks served as conceptual chains that bound the prisoners to the Hollerith machines that parsed their unique human essence into social, economic, and ethnic categories. Categories are key to both exalting and marginalizing others. “Most categorization” observed George Lakoff, “is automatic and unconscious, and if we become aware of it all, it is only in problematic cases” (Lakoff, 1986, p. 6).

Latent stereotypes and prejudices that people in power hold become known only when these cognitive constructs are converted into spoken words, mandated policies, and/or violent acts. The problematic case of the undesirable elements for Hitler, for example, was a dilemma first of the mind, of a conscious categorization that needed resolution through higher awareness of the menace he felt the Jews represented to the purity of the larger culture and society. This was done, partly, by making unspoken feelings overt. While serving as propaganda minister, Joseph Goebbels crafted the leading narratives that served to position Jews and other undesirables into the non-human category. Paralleling the modification of public perception through media was the work of the tabulating machines that placed captured people under the watchful eyes and hands of authorities refining the tools for the Final Solution.

According to Theodore Porter, “One of the tasks of history is to identify the sources of what enthusiasts proclaim to be utterly new and revolutionary” (2016). Edwin Black discovered in the historical records how IBM's Hollerith machine had revolutionized efficiency in dealing with the tedious routines and levels of attention that massive amounts of census data demanded. Vast numerical data sets could, at last, be manipulated in ways that made abstract numbers into more meaningful portraits of real people. This amazing new world of mass data came to integrate the weird with the banal, the conceptual with the material, and innovation with the commonplace.

Black wonders why IBM had involved itself in the market of fascist death camps. “It was never about anti-Semitism,” he argues, “never about Nazism; it was always about the money.” It was death made lucrative for a particular kind of free market. While the blind pursuit of money molds the fruit of human activity into products for mass-consumption in the open market, that passionate pursuit of mammon, in contemporary life, threatens paradoxically to remake humans, in part or whole, into salable and disposable commodities.

Referring to this process as “the third wave of marketization,” Michael Burawoy speaks of current markets where even “parts of the human body … have become commodities that are bought and sold” (Burawoy, 2017). If imprisonment and slavery, therefore, began with the Auschwitz inmate tattooed with an analog Hollerith number (as Black's research reveals), the new slavery will end with a concentration camp prisoner microchipped in the global matrix with a digital number. The tools of the matrix are, at present, appearing everywhere, the smart cameras and sensors of the real world augmented by the goggles of virtual reality in the Internet of Things (IoT). They are pushed upon the people in clever marketing campaigns by the power elite. This inexorable march toward voluntary slavery in a new order of global economics should arrive as no surprise to those who have watched with unease the tools of big data applied to all products and commodities, both organic and inorganic.

As a 12-digit numeric identifier, the Universal Product Code (UPC) first appeared in 1971 for items of trade. The ubiquitous IBM design for the UPC we see today revolutionized the tracking and control of all material inventory at point of sale. Not long thereafter, the bar code (as it's known) began appearing in tags for livestock. In most cases, a mark (or brand) on an animal is prima facie proof of ownership. Today, the mark of ownership is the new IBM/Sony “PersonalCell” chip—a radio-frequency identification chip (RFID), “smaller than a grain of rice” (Abate, 2014) and implantable under the skin, not only in livestock and pets but, most significantly, in humans. Does the implantable chip effectively lay the groundwork for a totalitarian dystopia?

Jefferson Graham reminds us that human beings are seen as no more than pets by the power elite, “You will get chipped—eventually,” (Graham, 2019) he notes. The headline casts the new tools as autonomous threats to human agency and sovereignty as the dogs of war unleashed on enemies tear into their victims. “The trend,” notes Lee Brown, “coincides with Sweden's march toward going cashless, with notes and coins making up just 1 percent of Sweden's economy” (Associated Press, 2017; Savage, 2018; Brown, 2019). Much of the discourse surrounding threats to the system (Broudy and Tanji, 2018) and to human agency and sovereignty is infused with the imagery of war that pits man against his machines.

The mainstream propaganda largely obscures, however, the designs of the agents behind the war, the network of technocratic profiteers whose talking points dominate the public discourse. With unfettered access to the mainstream media they own, the Technocrats writing the scripts for the new economy manage and manipulate “information in [this] data-driven world… recognized now as exciting, sexy, and consummately modern. And not for the first time,… At least since print culture, the thrill of data has been linked to brave new technologies” (Porter, 2016). The implantable chip is a brave new tool whose use is now being normalized in the corporate news media. Its claimed efficiencies are cast as so exciting and vital that no one in the mainstream critically questions where these tools will take humankind.

In its 2010, Scenarios for the Future of Technology and International Development, the president of the Rockefeller Foundation observed that, “One important—and novel—component of our strategy toolkit is scenario planning, a process of creating narratives about the future based on factors likely to affect a particular set of challenges and opportunities” (Rodin, 2010, p. 4). The elite storytellers need a global audience to take careful heed of the latest narratives they craft.

Conclusion

We close with a reflection on history, for readers to consider, when the specter of a technocratic dystopia began appearing in the context of the emerging “military-industrial complex” (Eisenhower, 1961). Aldous Huxley had forewarned the world 4 years before President Dwight D. Eisenhower's famous farewell message that alerted citizens to a new threat to peace. Huxley's interview with journalist Mike Wallace foretells a time when public relations messaging controlled by the power elite would threaten to undermine man's capacity to reason and, thus, like a Trojan Horse open the way for attacks on human rights and sovereignty. Huxley begins with the presupposition, elaborated earlier by Walter Lippmann, that leaders must “manufacture [the] consent” (Lippmann, 1922, p. 248) of the people they govern.

… if you want to preserve your power indefinitely, you have to get the consent of the ruled, and this they will do partly by drugs as I foresaw in Brave New World, partly by these new techniques of propaganda (Huxley, 1958).

Even a glance at the United States' ever-increasing obsession with prescriptions and medications since the early 1960s, and the rise of an American pharmaceutical hegemony, will apprise the casual observer that vast swaths of the populous have been rendered docile and comfortably numb, silenced, sedated and marginalized over decades of “massive over-prescription” (Frances, 2012; Insel, 2014).

“They will do it,” notes Huxley, “by bypassing the sort of rational side of man and appealing to his subconscious and his deeper emotions, and his physiology even, and so making him actually love his slavery” (1958). With the plethora of personal home assistants from Amazon, Apple, Google, Microsoft, Facebook, et al., now appearing in countless homes, the deep universal yearning for social connection, safety, and security has now been attended to through constant eavesdropping by the leading merchants, marketers, and the state (Broudy and Klaehn, 2019; Fowler, 2019). With the ever-present fear of some new menacing terror mythologized in mainstream media by the leading propagandists allayed by easy, efficient, and ubiquitous access to goods and service, people remain “highly susceptible to accepting extreme emergency measures” (Robinson, 2020). “I mean, I think, this is the danger that actually people may be, in some ways, happy under the new regime, but that they will be happy in situations where they oughtn't to be happy” (Huxley, 1958).

In 1944, Karl Polanyi saw three “fictions” in operation that made such a market economy work: (a) human life could be subordinated to market demands and reconstituted as ‘labor’; (b) the natural world could be subordinated to and reconstituted as ‘real estate’; and (c) the action of exchange could be reconstituted in ‘capital’. All life, nature, and exchange were transformed into things marked for profitability. “Such an institution could not exist for any length of time,” Polanyi argued, “without annihilating the human and natural substance of society” (Polanyi, 1944/2001, p. 3). Today, Michael Rectenwald sees Polanyi's “great transformation” as a Google Archipelago where “Big Digital” threatens human sovereignty with its “extended capabilities for supervision, surveillance, recording, tracking, facial-recognition, robot-swarming, monitoring, corralling, social-scoring, trammeling, punishing, ostracizing, un-personing or otherwise controlling populations…” (2019, p. 30).

As of this writing, we see in the present so-called “COVID-19 Plandemic”/a psychological, highly criminal lie planned down to the smallest detail, brought about with omnipresent fear, violence, non-lawful prosecutions and prohibitions, catastrophic hospital protocols, absolutely damaging drug cocktails, aggressive ventilation that massively damages the lungs(Oxygen toxicity, also known as oxygen poisoning, is lung damage that is caused by breathing in too much extra oxygen. Oxygen toxicity is a risk for people who are using medical oxygen. The effects are harmful when the patient breathes in too much molecular oxygen at increased partial pressure. It can cause several symptoms, including trouble with breathing and coughing. In severe cases, oxygen toxicity can even lead to death!!), and 100% FALSE tests, etc. etc., a clear path toward the “Brave New World” of “Big Digital”—the planned disappearance of hard currency and its replacement implanted in people mandated to be socially distant, the Microchip as big-tech savior resurrected by the “super-predators, [with] no conscience, no empathy [aiming to] bring [all] to heel” (Clinton, 1996). Although, as we have discussed, friendly fascism appears in various guises, it remains especially “hard for many to perceive Bill Gates as a dangerous authoritarian as well as a eugenics zealot” wearing “those pastel sweaters and that goofy grin, sound[ing] more like Kermit the Frog than Adolf Hitler and lard[ing] his public talks with altruistic-sounding bytes” (Frank, 2009; Harlow, 2009; Miller, personal communication). But, we urge readers to contemplate the efforts, “backed by the Bill & Melinda Gates Foundation,” and others now underway to invade the inviolable sovereign integrity of human beings with “injectable nanoparticles that reveal private information” (Wu, 2019).

Since the release of Windows 3.0. in 1990, the relentless fight against viruses continues. We wonder what it will really cost us all to inoculate ourselves from the sort of monopolistic savagery now inspiring the construction of the global “control grid” (Eclinik, 2019) and adjuring us to accept the newfangled injectable solutions.

https://web.archive.org/web/20230901133013/https://www.uni-kiel.de/psychologie/mausfeld/pubs/Mausfeld_Why%20do%20the%20lambs%20remain%20silent_2015.pdf

https://www.bitchute.com/video/g0mV3B5WYsTX/

A brave Australian funeral director speaks out: A brave Australia funeral director speaks out about the tragic rise in sudden deaths in young people, turbo cancers and the loss of babies.

A considerable increase in miscarriages, deformities and a pattern of no brain development with hospital workers also saying ‘I’ve never seen so many babies’

Colleagues have commented on a rise in baby funerals from one a month to four a week.

https://researchandappliedmedicine.com/revistas/vol2/revista2/canada-ingles.pdf

17 millions+

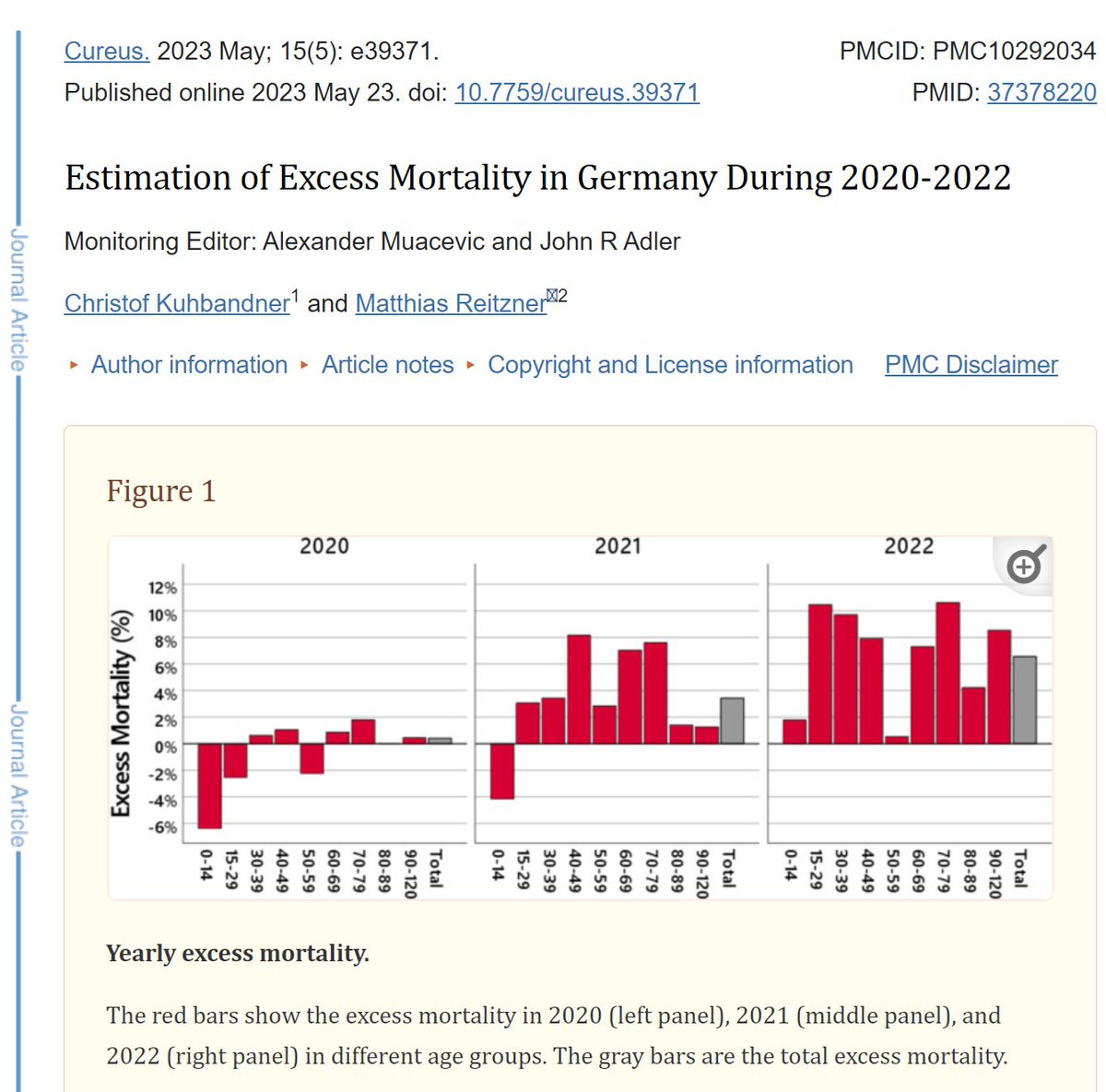

https://pmc.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/articles/PMC10292034/

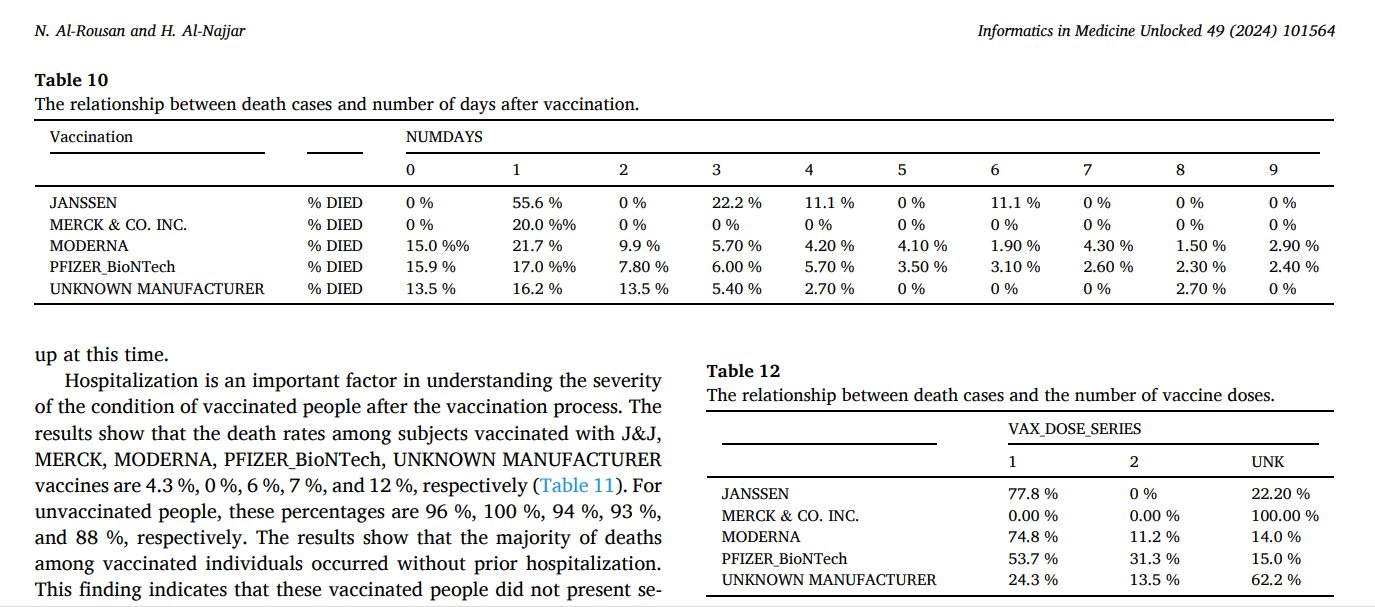

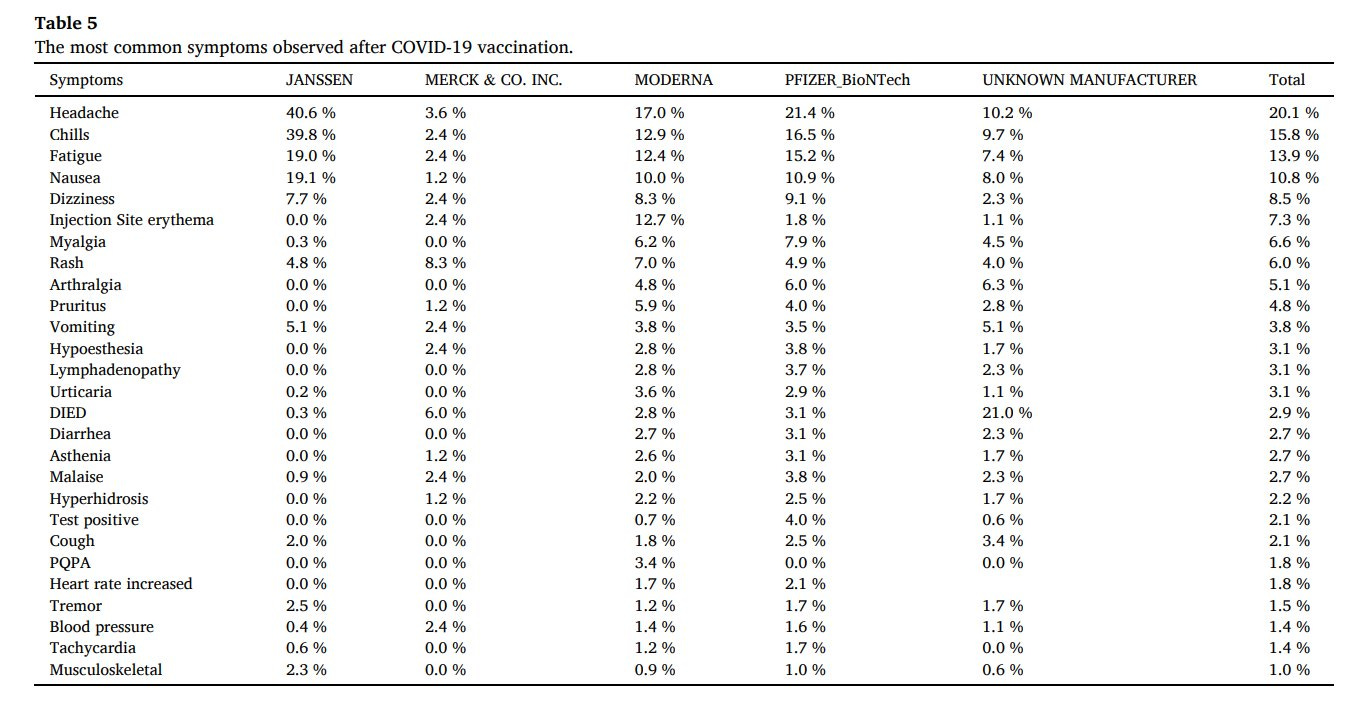

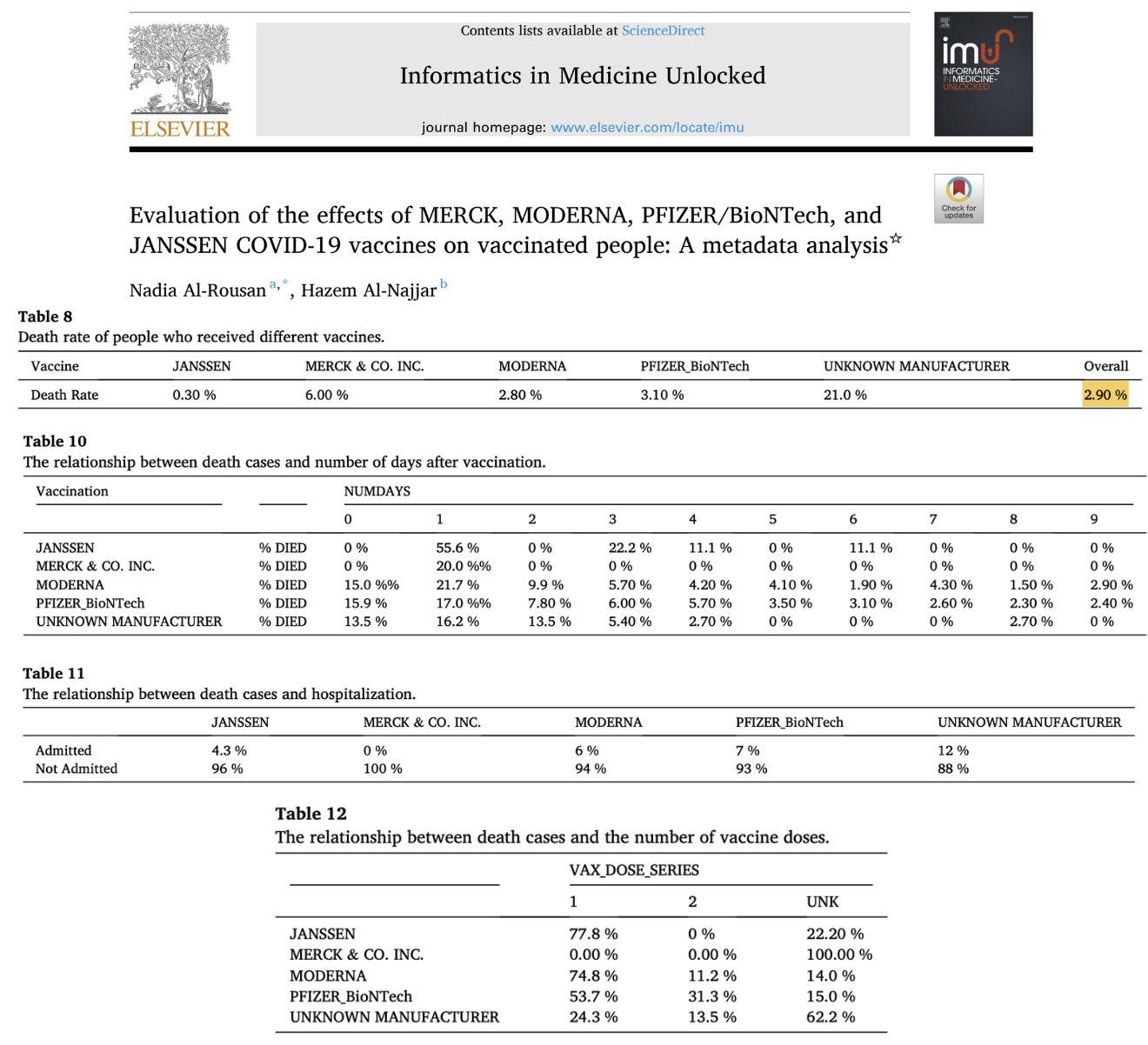

https://www.sciencedirect.com/science/article/pii/S2352914824001205

150 million DEAD - THAT is only 3% that were actually recorded - and now let's think of all those who died and were NOT registered, because the rule at the CDC and all over the world was: after the first dose of poison, the person is considered “not vaccinated”.... a mass murder of superlatives for which there are simply no suitable adjectives!!!!

But read here:

https://correlation-canada.org/wp-content/uploads/2024/07/2024-07-19-Correlation-ACM-World-125-countries-Rancourt-Hickey-Linard.pdf

This report, which consists of 521 pages including hundreds of figures, contains a detailed examination of excess all-cause mortality during the so-called "Covid period"=MASS MURDER in 125 countries comprising approximately 35% of the world’s population - (2.70 billion of 7.76 billion, in 2019).

They describe plausible mechanisms and argue that the three primary causes of death associated with the excess all-cause mortality during (and after) the so-called "Covid period" are:

Biological (including psychological) stress from mandates such as lockdowns and associated socio-economic structural changes - such as e.g. suicides

Non-COVID-19-vaccine medical interventions such as mechanical ventilators and drugs (including denial of treatment with antibiotics)

COVID-19 “vaccine” = a poisoning with different batches!!

https://fbf.one/wp-content/uploads/2021/12/Pfizer-Batch-Codes-and-Toxicity-Levels.pdf

Pfizer Batch Codes and Toxicity Levels

injection rollouts, including repeated rollouts on the same populations

A planned and deliberately induced mass murder - and the dying of the people will not end....

etc. etc. etc.

https://rumble.com/v5bpyvh-died-suddenly.html

and from ca. 58:00 it becomes especially frightening and infinitely sad!!! Dr. Thorp

Dr. Thorp spoke about it early on, only people didn't want to know.... because they were brought into a perpetual psychosis by a constant propagandized fear based on impertinent lies, manipulation and deceit, so that this mass murder took its course.....

VAERS Report Regarding Spontaneous Abortion & Fetal Death: ca 300 already on 05/14/2021

THIS is so highly criminal that I would like to tear each and every one in the air!!!! You all belong for the rest of your shitty life locked in a deep hole, only with water and bread and otherwise absolutely nothing!!!!! Anyone who causes THAT and silently accepts it is NOT A HUMAN BEING in my opinion and should ALSO NOT BE NAMED AS SUCH!!!! YOU ALL are the SCUM of humanity!!!😡😡😡

https://web.archive.org/web/20211208124143/https://sgtreport.com/2021/11/pandemic-payoff-bill-gates-injected-319-million-into-mainstream-media/

A huge amount of blood money was spent to create and establish this impertinent, highly criminal and inhuman lie!

Additional information was revealed this week which shows the full extent of Gates’ hold over the mainstream media, based on over 30,000 individual grants from the Bill and Melinda Gates Foundation’s own website database.

The beneficiaries include the biggest names in mainstream media, including CNN, BBC, NBC, NPR, PBS, The Guardian, France’s Le Monde, The Financial Times, The Daily Telegraph, Germany’s Der Spiegel, the Conversation, Education Week, the Education Post, the Financial Times, the Texas Tribune, Al-Jazeera, the Atlantic, and New York Public Radio.

The top winners include $24.6 million for Washington’s state-run media outlet NPR, $12.9 million for The Guardian, and $10.8 million for Seattle-based Cascade Public Media, which owns local station KCTS-TV.

Alan McLeod from Mint Press News writes…

While other billionaires’ media empires are relatively well known, the extent to which Gates’s cash underwrites the modern media landscape is not. After sorting through over 30,000 individual grants, MintPress can reveal that the Bill and Melinda Gates Foundation (BMGF) has made over $300 million worth of donations to fund media projects.

Recipients of this cash include many of America’s most important news outlets, including CNN, NBC, NPR, PBS and The Atlantic. Gates also sponsors a myriad of influential foreign organizations, including the BBC, The Guardian, The Financial Times and The Daily Telegraph in the United Kingdom; prominent European newspapers such as Le Monde (France), Der Spiegel (Germany) and El País (Spain); as well as big global broadcasters like Al-Jazeera.

The Gates Foundation money going towards media programs has been split up into a number of sections, presented in descending numerical order, and includes a link to the relevant grant on the organization’s website.

Awards Directly to Media Outlets:

NPR- $24,663,066

The Guardian (including TheGuardian.org)- $12,951,391

Cascade Public Media – $10,895,016

Public Radio International (PRI.org/TheWorld.org)- $7,719,113

The Conversation- $6,664,271

Univision- $5,924,043

Der Spiegel (Germany)- $5,437,294

Project Syndicate- $5,280,186

Education Week – $4,898,240

WETA- $4,529,400

NBCUniversal Media- $4,373,500

Nation Media Group (Kenya) – $4,073,194

Le Monde (France)- $4,014,512

Bhekisisa (South Africa) – $3,990,182

El País – $3,968,184

BBC- $3,668,657

CNN- $3,600,000

KCET- $3,520,703

Population Communications International (population.org) – $3,500,000

The Daily Telegraph – $3,446,801

Chalkbeat – $2,672,491

The Education Post- $2,639,193

Rockhopper Productions (U.K.) – $2,480,392

Corporation for Public Broadcasting – $2,430,949

UpWorthy – $2,339,023

Financial Times – $2,309,845

The 74 Media- $2,275,344

Texas Tribune- $2,317,163

Punch (Nigeria) – $2,175,675

News Deeply – $1,612,122

The Atlantic- $1,403,453

Minnesota Public Radio- $1,290,898

YR Media- $1,125,000

The New Humanitarian- $1,046,457

Sheger FM (Ethiopia) – $1,004,600

Al-Jazeera- $1,000,000

ProPublica- $1,000,000

Crosscut Public Media – $810,000

Grist Magazine- $750,000

Kurzgesagt – $570,000

Educational Broadcasting Corp – $506,504

Classical 98.1 – $500,000

PBS – $499,997

Gannett – $499,651

Mail and Guardian (South Africa)- $492,974

Inside Higher Ed.- $439,910

BusinessDay (Nigeria) – $416,900

Nutopia- $350,000

Independent Television Broadcasting Inc. – $300,000

Independent Television Service, Inc. – $300,000

Caixin Media (China) – $250,000

Pacific News Service – $225,000

National Journal – $220,638

Chronicle of Higher Education – $149,994

Belle and Wissell, Co. $100,000

Media Trust – $100,000

New York Public Radio – $77,290

KUOW – Puget Sound Public Radio – $5,310

Together, these donations total $166,216,526. The money is generally directed towards issues close to the Gateses hearts. For example, the $3.6 million CNN grant went towards “report[ing] on gender equality with a particular focus on least developed countries, producing journalism on the everyday inequalities endured by women and girls across the world,” while the Texas Tribune received millions to “to increase public awareness and engagement of education reform issues in Texas.” Given that Bill is one of the charter schools’ most fervent supporters, a cynic might interpret this as planting pro-corporate charter school propaganda into the media, disguised as objective news reporting.

The Gates Foundation has also given nearly $63 million to charities closely aligned with big media outlets, including nearly $53 million to BBC Media Action, over $9 million to MTV’s Staying Alive Foundation, and $1 million to The New York Times Neediest Causes Fund. While not specifically funding journalism, donations to the philanthropic arm of a media player should still be noted.

Gates continues to underwrite a wide network of investigative journalism centers as well, totaling just over $38 million, more than half of which has gone to the D.C.-based International Center for Journalists to expand and develop African media.

These centers include:

International Center for Journalists- $20,436,938

Premium Times Centre for Investigative Journalism (Nigeria) – $3,800,357

The Pulitzer Center for Crisis Reporting – $2,432,552

Fondation EurActiv Politech – $2,368,300

International Women’s Media Foundation – $1,500,000

Center for Investigative Reporting – $1,446,639

InterMedia Survey institute – $1,297,545

The Bureau of Investigative Journalism – $1,068,169

Internews Network – $985,126

Communications Consortium Media Center – $858,000

Institute for Nonprofit News – $650,021

The Poynter Institute for Media Studies- $382,997

Wole Soyinka Centre for Investigative Journalism (Nigeria) – $360,211

Institute for Advanced Journalism Studies – $254,500

Global Forum for Media Development (Belgium) – $124,823

Mississippi Center for Investigative Reporting – $100,000

In addition to this, the Gates Foundation also plies press and journalism associations with cash, to the tune of at least $12 million. For example, the National Newspaper Publishers Association — a group representing more than 200 outlets — has received $3.2 million.

The list of these organizations includes:

Education Writers Association – $5,938,475

National Newspaper Publishers Association – $3,249,176

National Press Foundation- $1,916,172

Washington News Council- $698,200

American Society of News Editors Foundation – $250,000

Reporters Committee for Freedom of the Press- $25,000

This brings our running total up to $216.4 million.

The foundation also puts up the money to directly train journalists all over the world, in the form of scholarships, courses and workshops. Today, it is possible for an individual to train as a reporter thanks to a Gates Foundation grant, find work at a Gates-funded outlet, and to belong to a press association funded by Gates. This is especially true of journalists working in the fields of health, education and global development, the ones Gates himself is most active in and where scrutiny of the billionaire’s actions and motives are most necessary.

Gates Foundation grants pertaining to the instruction of journalists include:

Johns Hopkins University – $1,866,408

Teachers College, Columbia University- $1,462,500

University of California Berkeley- $767,800

Tsinghua University (China) – $450,000

Seattle University – $414,524

Institute for Advanced Journalism Studies – $254,500

Rhodes University (South Africa) – $189,000

Montclair State University- $160,538

Pan-Atlantic University Foundation – $130,718

World Health Organization – $38,403

The Aftermath Project- $15,435

The BMGF also pays for a wide range of specific media campaigns around the world. For example, since 2014 it has donated $5.7 million to the Population Foundation of India in order to create dramas that promote sexual and reproductive health, with the intent to increase family planning methods in South Asia. Meanwhile, it alloted over $3.5 million to a Senegalese organization to develop radio shows and online content that would feature health information. Supporters consider this to be helping critically underfunded media, while opponents might consider it a case of a billionaire using his money to plant his ideas and opinions into the press.

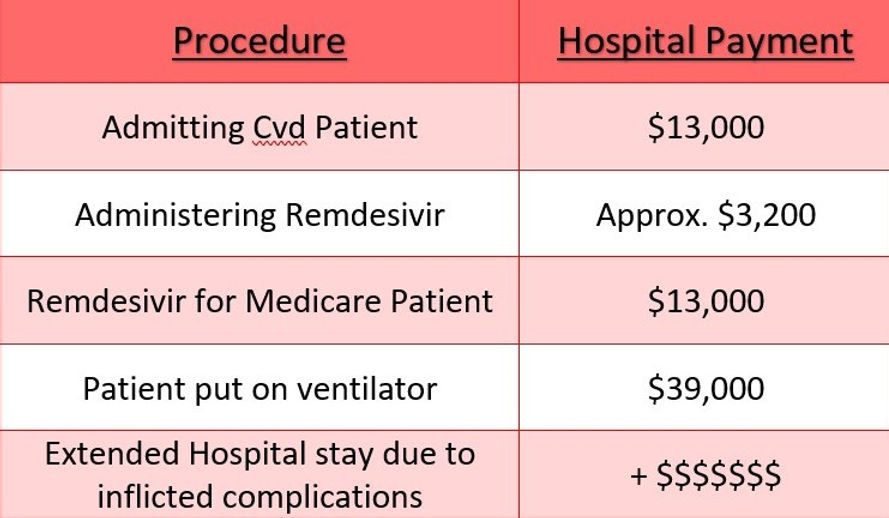

https://www.protocolkills.com/hospital-protocol

https://web.archive.org/web/20211227213518/https://www.thedesertreview.com/opinion/columnists/hospital-death-camps-exposed/article_97776276-674f-11ec-85d0-f33f634331c8.html

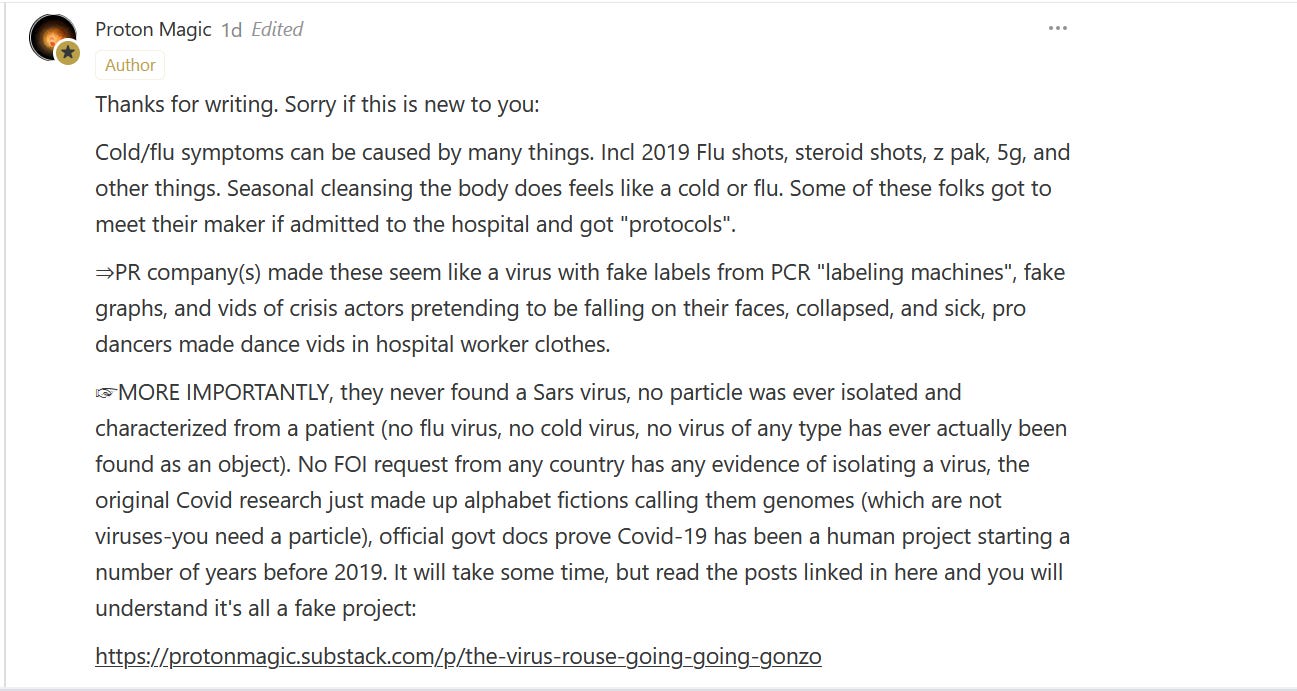

If you're reading this, it's with the knowledge that there has NEVER been a “virus”!!!! Because this crime/mass murder began with this highly criminal lie, which EVERYONE has supported!!!!

Everything has been written or explained - someone who is really interested in the facts can have a look/read on all of mine articles or at Proton Magic, Ray Horvath etc.(not for everything, of course!!) - or start researching for yourself - don't continue to be lied to by people who didn't mean well in the first place and who took part in this highly criminal lie, but now pretend to want to help people when it is already too late for countless millions/billions.... there are so many here on SS where you can smell the falseness and deceitfulness through the internet and who try to hide their ignorance coldly through this deceitfulness without even once thinking of another person/people and their suffering....

etc. - thank you all so much for your interest and stay strong, self-confident, without fear and a united wall that holds together and can never be divided again - protect your children, yourselves and your family members, friends etc.!!!❤️❤️❤️