THE TRUTH IS ALWAYS ON THE OTHER SIDE

Science and technology roadmap for graphene, related two-dimensional crystals, and hybrid systems - Part 1

https://pubs.rsc.org/am/content/articlehtml/2015/nr/c4nr01600a?page=search#sect6449

1. Introduction

The primary objective of this roadmap is to guide the community towards the development of products based on graphene, related two dimensional (2d) crystals and hybrid systems. For simplicity we will refer to this new materials platform as graphene and related materials and use the acronym GRM. These have a combination of properties that could make them key enablers for many applications, generating new products that cannot (or may be difficult to) be obtained with current technologies or materials. The creation of new disruptive technologies based on GRMs is conditional to reaching a variety of objectives and overcoming several challenges throughout the value chain, ranging from materials to components and systems.

The main scientific and technological objectives are:

A) Material technologies

○ Identification of new layered materials (LMs) and assessment of their potential.

○ Reliable, reproducible, sustainable and safe, large scale production of GRMs, satisfying the specific needs of different application areas.

B) Component technologies

○ Identification of new device concepts enabled by GRMs.

○ Identification of component technologies that utilize GRMs.

○ Electronic technologies, comprising high frequency electronics, optoelectronics, spintronics and sensors.

C) Systems integration

○ Route to bring components and structures based on GRMs to systems capable of providing new functionalities and open new application areas.

○ New concepts for integrating GRMs in existing technology platforms.

○ Integration routes for nanocomposites, flexible electronics and energy applications.

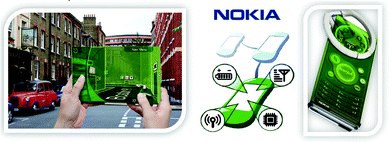

Our science and technology roadmap (STR) outlines the principal routes to develop the GRM knowledge base and the means of production and development of new devices, with the final aim of integrating GRMs into systems. In the Information and Communications Technology (ICT) area, the STR focuses on technology that will enable new applications, such as the Morph concept1 (Fig. 1a), which exploits the electrical, optical and mechanical properties of GRMs to realize new types of personal communicators. In the domain of physical communication, the STR targets several key technologies in energy production and storage, as well as new functional light-weight composites. These are to be integrated in transportation systems, such as new airplanes, buses, cars (as illustrated by the SmartForVision concept electric car,2Fig. 1b). The STR also considers areas such as Health and Energy. By exploiting the GRM's unique electrical and optical properties, the STR will highlight the directions towards the development of novel systems for information processing and communications.

Fig. 1 Morph1 (left) and SmartForVision2 (right) are examples of visionary applications where GRMs’ unique properties might be combined to enable new products.

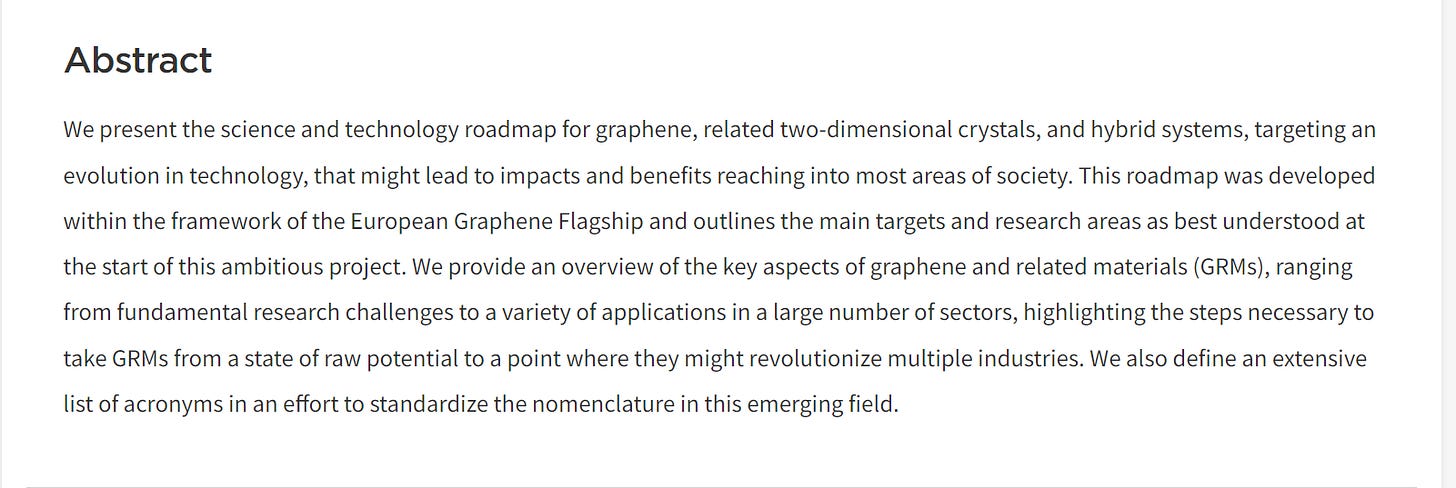

The STR is divided in 11 thematic chapters, summarized in Fig. 2. Each of them comprises a dedicated timeline. A final chapter presents two overall summary roadmaps.

Fig. 2 Symbols associated with each theme. In the document, the symbol

is associated/replaced by the symbol

when we refer to industrial/large scale production.

The present STR may not be fully complete, leaving out some of the most recent and rapidly evolving areas. We plan to present regular updates over the next 10 years to keep abreast with the latest developments in GRM science and technology. These include charge-based high speed electronic devices, as well as non-charge-based devices (e.g. spintronic devices) with novel functionalities. A key area is advanced methods to produce GRMs, combining structural functions with embedded electronics in an environmentally sustainable manner. The STR extends beyond mainstream ICT to incorporate novel sensor applications and composites that take advantage of the GRMs chemical, biological and mechanical properties. Beyond ICT, the STR reaches out to several related areas. Graphene's high electrical conductivity, σ, and large surface area per unit mass make it an interesting material for energy storage, e.g. in advanced batteries and supercapacitors. These could have a large impact on portable electronics and other key areas, such as electric cars. The prospect of rapidly chargeable lightweight batteries would give environmentally friendly transportation a push and advance the large scale implementation of electric cars as a key component in urban and suburban transport. Strong and lightweight composites would also allow us to build new cars, airplanes and other structures using less material and energy, and contribute directly to a more sustainable world, see Fig. 3.

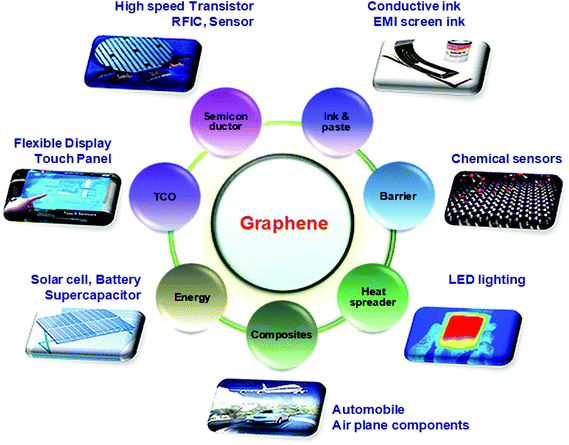

Fig. 3 Overview of Applications of Graphene in different sectors ranging from conductive ink to chemical sensors, light emitting devices, composites, energy, touch panels and high frequency electronics.

1.1. Graphene-based disruptive technologies: overview

Technologies, and our economy in general, usually advance either by incremental developments (e.g. scaling the size and number of transistors on a chip) or by quantum leaps (transition from vacuum tubes to semiconductor technologies). Disruptive technologies, behind such revolutions, are usually characterised by universal, versatile applications, which change many aspects of our lives simultaneously, penetrating every corner of our existence. In order to become disruptive, a new technology needs to offer not incremental, but orders of magnitude improvements. Moreover, the more universal the technology, the better chances it has for broad base success. This can be summarized by the “Lemma of New Technology”, proposed by Herbert Kroemer, who received the Nobel Prize in Physics in 2000 for basic work in ICT: “The principal applications of any sufficiently new and innovative technology always have been – and will continue to be – applications created by that technology”.3 Graphene is no exception to this lemma. Does graphene have a chance to become the next disruptive technology? Can graphene be the material of the 21st century?

In terms of its properties, it certainly has potential. The 2010 Nobel Prize in Physics already acknowledged the profound novelty of the physical properties that can be observed in graphene: different physics applies, compared with other electronic materials, such as common semiconductors. Consequently, a plethora of outstanding properties have arisen from this material. Many are unique and superior to those of other materials. More importantly, such combination of properties cannot be found in any other material or material system. So, it is not a question of if, but a question of how many applications will graphene be used for, and how pervasive will it become. There are indeed many examples of “wonder” materials that have not yet lived up to expectations, nor delivered the promised revolution, while more “ordinary” ones are now pervasively used. Are the properties of graphene so unique to overshadow the unavoidable inconveniences of switching to a new technology, a process usually accompanied by large research and development (R&D) and capital investments? The advancing R&D activity on GRMs has already shown a significant development aimed at making GRMs suitable for industrial applications.

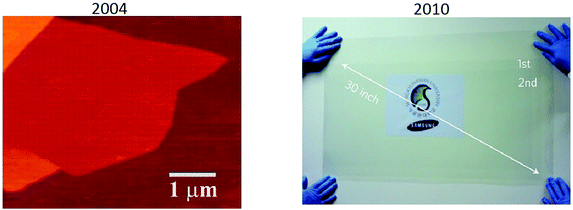

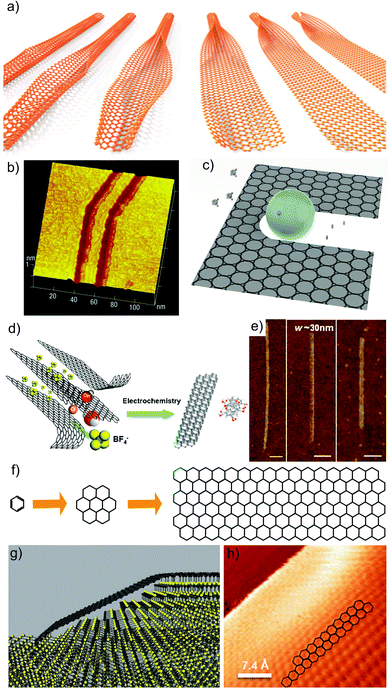

The production of graphene is one striking example of rapid development, with progress from random generation of micro-flakes in the laboratory5 to large-scale,6 roll-to-roll (R2R) processing of graphene sheets of sizes approaching the metre-scale7 (Fig. 4).

Fig. 4 Rapid evolution of graphene production: from microscale flakes4 to roll-to-roll processing.7

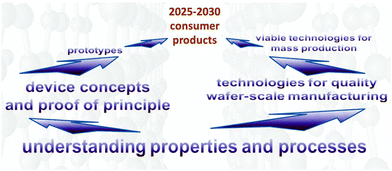

It is reasonable to expect a rapid clearing of further technological hurdles towards the development of a GRM-based industry in the coming years (Fig. 5).

Fig. 5 Towards GRM-based products.

Therefore, in spite of the inherent novelty associated with GRMs and the lack of maturity of GRM technology, an initial roadmap can be envisaged, including short-term milestones, and some medium- to long-term targets, less detailed, but potentially more disruptive. This should guide the expected transition towards a technological platform underpinned by GRMs, with opportunities in many fields and benefits to society as a whole.

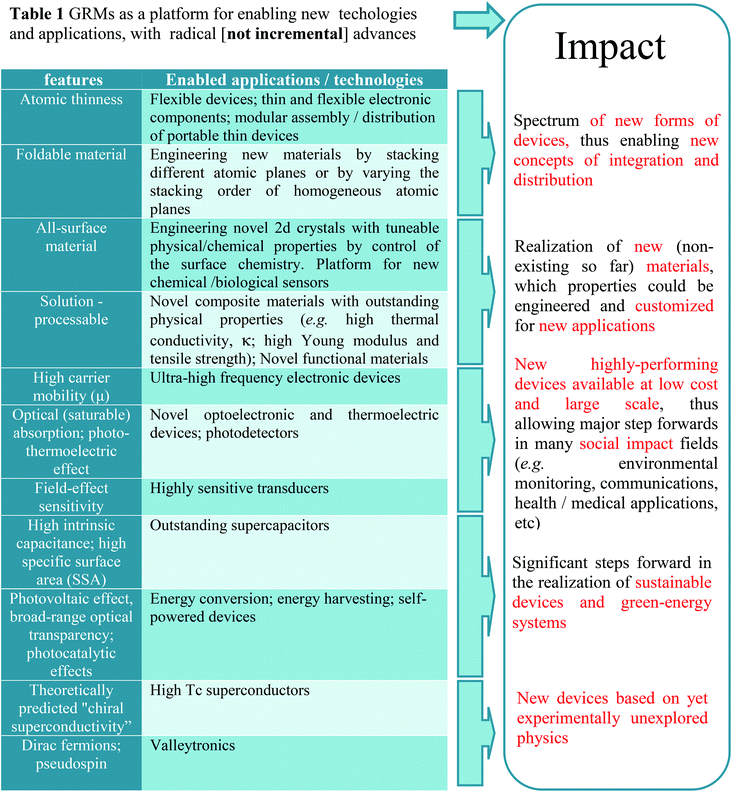

1.1.1. Opportunities. GRMs are expected to have a major impact in several technological fields (see Table 1), due to the new applications enabled by their properties. E.g., potential electronic applications include high-frequency devices, touch screens, flexible and wearable devices, as well as ultrasensitive sensors, nano- electromechanical systems (NEMS), super-dense data storage, photonic devices, etc. In the energy field, applications include batteries and supercapacitors to store and transport electrical power, and solar cells. However, in the medium term, some of graphene's most appealing potential lies in its ability to transmit light as well as electricity, offering improved performance for light emitting diodes (LEDs), flexible touch screens, photodetectors, and ultrafast lasers.

The upscaling of GRM production is steadily progressing, and challenges remain when it comes to maintaining the properties and performance upon up-scaling, which includes mass production for material/energy-oriented applications and wafer-scale integration for device/ICTs-oriented applications. Nevertheless, GRMs technology is expected to provide opportunities for the development of a novel platform, contributing to key technological fields with important social and economic impacts. The definition of “quality” of a GRM cannot be given in absolute terms, but strictly depends on the applications. E.g. the “quality” of graphene needed for high performance electronics is “the opposite” of that required for batteries or supercapacitors, in that the latter work better with materials having defects, voids and cavities, while the former require defect free, and flat material. This will be a challenge for standardization, since the materials properties will have to be defined in relation to a variety of possible applications.

1.1.1.1. New opportunities for electronics. The introduction of more functions in integrated electronic systems will enable applications in domotics (i.e. home automation by means of distributed sensors, actuators and controllers), environmental control, and office automation to meet the social request for better safety, health and comfort. An increase in automation should also consider the aging population and people at work, and the need of adequate facilities. Sensors or metrological devices based on GRMs can further extend functionalities of hybrid circuits. Three dimensional (3d) integration of GRMs-based devices may be conceivable in a Si flow, and could be the solution for low cost chips with extended functionalities.

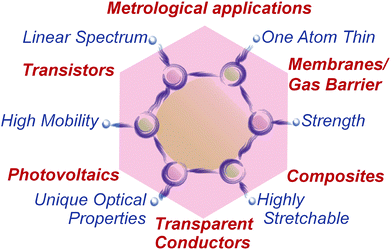

Graphene has many record properties, see Fig. 6. It is transparent like (or better than) plastic, but conducts heat and electricity better than any metal, it is an elastic film, behaves as an impermeable membrane, and it is chemically inert and stable. Thus it seems ideal as the next generation transparent conductor. There is a real need to find a substitute for indium tin oxide (ITO) in the manufacturing of various types of displays and touch screens, due to the brittleness of indium that makes it difficult to use them when flexibility is a requirement.8 Graphene is an ideal candidate for such a task.9 Thus, coupled with carbon's abundance, this presents a more sustainable alternative to ITO. Prototypes of graphene-based displays have been produced7 and commercial products seem imminent.10

Fig. 6 Graphene properties and application areas.

In 2010, the first R2R production of 30-inch graphene transparent conductors (TC), with low sheet resistance (Rs) and 90% transmittance (Tr), competitive with commercial transparent electrodes, such as ITO, was reported.7 Graphene electrodes have been incorporated into fully functional touch-screens capable of withstanding high strain.10 Thus, one can envision the development of flexible, portable and reconfigurable electronics, such as the MORPH concept1 (Fig. 1 and 7).

Fig. 7 NOKIA Morph:1 the future mobile device will act as a gateway. It will connect users to local environment, as well as the global internet. It is an attentive device that shapes according to the context. It can change its form from rigid to flexible and stretchable.1

New horizons have opened with the demonstration of high-speed graphene circuits11 offering high-bandwidth, which might impact future low-cost smart phones and displays.

Complementary metal oxide semiconductor (CMOS) technology, as currently used in integrated circuits, is rapidly approaching the limits of downsizing transistors,12 and graphene is considered a possible candidate for post-Si electronics by the International Technology Roadmap for Semiconductors (ITRS).12 However, a graphene-based low power device meeting all of the requirements of CMOS technology has not been demonstrated yet. The technology needed to produce graphene circuits is still in its infancy, and growth of large area films with good electrical properties on flat dielectric surfaces has not yet been demonstrated. Novel architectures,13,14 not necessarily based on graphene ribbons,15 need to be developed.

In 2011 ref. 11 reported the first wafer-scale graphene circuit (broadband frequency mixer) in which all components, including graphene field-effect transistors (GFETs) and inductors, were integrated on a single SiC wafer. The circuit operated as a broadband Radio Frequency (RF) mixer at frequencies up to 10 GHz, with thermal stability and little reduction in performance (less than one decibel) in the temperature (T) range 300–400 K. This suggests that graphene devices with complex functionality and performance may be achieved.

Being just one atom thick, graphene appears as a suitable candidate to eventually realize a new generation of flexible electronic devices.14 Electronics on plastics or paper is low cost.16,17 It will offer the possibility to introduce more information on goods used on a daily basis, e.g. on food for safety and health, as well as on many other products. Bar codes may not be able to store all the required information. Magnetic strips or stand-alone memories do not offer the same opportunities as active electronics interacting in a wireless network. The possibility to develop passive components in GRMs (resistors, capacitors, antennas) as well as diodes (Schottky) or simple FETs, and the rapid growth of technology in this direction may enable RF flexible circuits in a wireless networked environment.

Thin and flexible GRMs-based electronic components might be obtained and modularly integrated, and thin portable devices might be assembled and distributed. Graphene can withstand mechanical deformation18 and can be folded without breaking.18 Such a feature provides a way to tune the electronic properties, through so-called “strain engineering”19 of the electronic band structure. Foldable devices can be imagined, together with a wealth of new device form factors, which could enable innovative concepts of integration and distribution.

By enabling flexible electronics, GRMs will allow the use of the existing knowledge base and infrastructures of various organizations working on organic electronics (organic LEDS as used in displays, conductive polymers, plastics, printable electronics), providing a synergistic framework for collecting and underpinning many distributed technical competences.

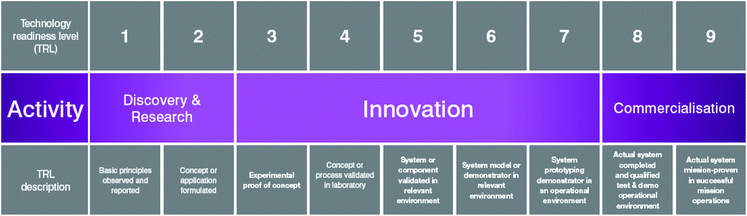

1.1.1.2. New energy solutions. GRMs could bring new solutions to the current challenges related to energy generation and storage, first in nano-enhanced products, then in new nano-enabled products. GRMs-based systems for energy production (photovoltaics, PV, fuel cells), energy storage (supercapacitors, batteries, and hydrogen storage) may be developed via relevant proof of concept demonstrators that will progress towards the targeted technology readiness levels (TRLs) required for industrial adoption. TRLs are used to assess the maturity of technologies during their development. The commonly used NASA scale,20,21 is shown in Fig. 8: 1. Basic principles observed and reported; 2. Technology concept and/or application formulated; 3. Analytical and experimental critical function and/or characteristic proof of concept; 4. Component and/or breadboard validation in laboratory environment; 5. Component and/or breadboard validation in relevant environment; 6. System/subsystem model or prototype demonstration in a relevant environment; 7. System prototype demonstration in an operational environment; 8. Actual system completed and qualified through test and demonstration. 9. Actual system proven through successful operations.

Fig. 8 TRL definitions, adapted from ref. 21.

Furthermore, graphene technology may provide new power management solutions, key to allow efficient and safe use of energy. To date in Europe nearly the 60% of the energy is electrical (lighting, electronics, telecommunications, motor control).22 Of the remaining 40%, nearly all is used for transportation.22

1.1.1.3. New technologies and materials: towards a novel technological platform. GRMs may favour not only an improvement of existing technologies, such as electronics and optoelectronics, but may also enable the emergence of new technologies, currently hampered by intrinsic limitations. The GRMs' properties, with a qualitatively different physics with respect to the other commonly used materials, may enable technological concepts, thus far only theoretically possible, but not practically developed.

One example is that of spintronics,23 an emerging technology that exploits the spin rather than the charge of electrons as the degree of freedom for carrying information,24 with the primary advantage of consuming less power per computation.25 Although one spintronic effect – namely, giant magnetoresistance26 – is already a fundamental working principle in hard disk technology,27 the use of spintronic devices as a replacement for CMOS has not been realized yet. Scientific papers have highlighted graphene properties that are suitable for the development of spintronic devices,28–30 and many groups are now pursuing this.

Radically new technologies could be enabled by graphene, such as the so-called “valleytronics”,31 which exploits the peculiar “isospin”31 of charge carriers in graphene as a degree of freedom for carrying information. Further, there are some still not experimentally proven theoretical predictions, such as a “chiral superconductivity”,32 which may lead to completely new applications.

Taking just these few examples into account, we expect that the development of some new applications based on the salient properties of GRMs might happen in the coming years.

Graphene is also an ideal candidate for engineering new materials, and many examples have already been realised.33–36 The “all-surface” nature of graphene offers the opportunity to tailor its properties by surface treatments (e.g. by chemical functionalization33). E.g., graphene has been converted into a band-gap semiconductor (hydrogenated graphene, or “graphane”33) or into an insulator (fluorinated graphene, or “fluorographene”34). In addition, graphene flakes can be placed in dispersions.35 These retain many of its outstanding properties, and can be used for the realisation of composite materials (e.g. by embedding in a polymeric matrix36,37) with improved performance.35–37

Graphene is not only important for its own properties, but also because it is the paradigm for a new class of materials, which is likely to grow following the rise of graphene technology. Some examples have already been reported, such as hexagonal boron nitride (h-BN)5,38 and molybdenite monolayers5,38,39 The crystal structure of the latter was studied since 1923 by Dickinson and Pauling,40 with studies extended to a few layers in the sixties (a possible observation of monolayer MoS2 reported in the pioneering work of Frindt in Cambridge in 1963)41,42 and a definite identification of monolayer MoS2 in 1986.39 The assembly of such 2d crystals, i.e. by stacking different atomic planes (heterostructures43), or by varying the stacking order of homogeneous atomic planes,44 provides a rich toolset for new, customised materials. We expect that the lessons learnt developing graphene science and technology will drive the manufacturing of many other innovative materials.

At present, the realisation of an electronic device (such as, e.g., a mobile phone) requires the assembly of a variety of components obtained by many different technologies. GRMs, by including many properties, may offer the opportunity to build a comprehensive technological platform for different device components, including transistors, batteries, optoelectronic components, detectors, photovoltaic cells, photodetectors, ultrafast lasers, bio- and physicochemical sensors, etc. Such a change in the paradigm of device manufacturing may open big opportunities for the development of a new industry.

1.2. Scientific output

GRM research is an example of an emerging translational nanotechnology, where discoveries in laboratories are transferred to applications. This is evidenced, in part, by the rise in patenting activity since 2007 by corporations around the world.45 The concept of translational technology is typically associated with biomedicine,46 where it is a well-established link between basic research and clinical studies, but the principle can be applied more generally. A striking example is giant magnetoresistance,47 that moved from an academic discovery to a dominant information storage technology in a few years.48 Similarly, GRMs have the potential to make a profound impact: Integrating GRMs components with Si-based electronics, and gradually replacing Si in some applications, allows not only substantial performance improvements but, more importantly, new applications.

Carbon has been the driving force behind several technological revolutions: in the 19th century, energy production by burning carbon was integral to the industrial revolution;49 in the 20th century, carbon-based plastics revolutionized the manufacturing industry;50 in the 21st century, graphitic carbon might be a key component in a third technological revolution.

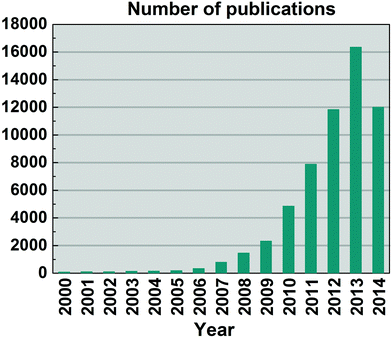

The growth of publications on GRMs is shown in Fig. 9, with no sign of slowing down. The reasons for the growth of research on GRMs are manifold. First, graphene is a material with a unique set properties. Either separately or in combinations, these can be exploited in many areas of research and applications; new possibilities are being recognized all the time as the science of GRMs progresses. Second, graphene Science and Technology (ST) relies on one of the most abundant materials on earth,51 carbon. It is an inherently sustainable and economical technology. Thirdly, graphene is a planar material and, as such, compatible with the established production technologies in ICT, and integrable with conventional materials such as Si. Combined, these premises give realistic promise of creating a new, more powerful and versatile, sustainable and economically viable technology platform. As a result, graphene research has already emerged as the top research front in materials science.52 However, due to the unique structure of graphene, many of the possibilities it offers are still poorly understood, and their analysis requires highly sophisticated methods; To quote the Nobel Laureate Frank Wilczek: «graphene is probably the only system where ideas from quantum field theory can lead to patentable innovations».46

Fig. 9 Publications on graphene from 2000 to Aug. 2014 (thus, well over 18000 are expected by end 2014). Source ISI Web of Science (search: Topic = Graphene). Publications on graphene prior to 2000 are not plotted.

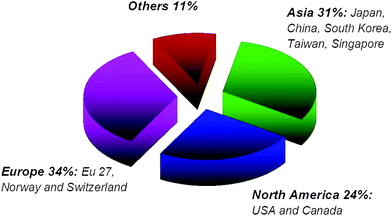

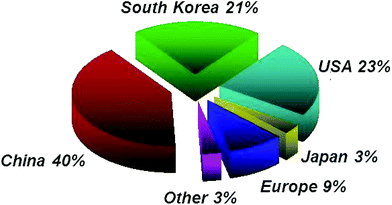

1.2.1. Intellectual property landscape analysis. In the graphene area, there has been a particularly rapid increase in patent activity from around 2007.45 Much of this is driven by patent applications made by major corporations and universities in South Korea and USA.53 Additionally, a high level of graphene patent activity in China is also observed.54 These features have led some commentators to conclude that graphene innovations arising in Europe are being mainly exploited elsewhere.55 Nonetheless, an analysis of the Intellectual Property (IP) provides evidence that Europe already has a significant foothold in the graphene patent landscape and significant opportunities to secure future value. As the underlying graphene technology space develops, and the GRM patent landscape matures, re-distribution of the patent landscape seems inevitable and Europe is well positioned to benefit from patent-based commercialisation of GRM research.

Overall, the graphene patent landscape is growing rapidly and already resembles that of sub-segments of the semiconductor and biotechnology industries,56 which experience high levels of patent activity. The patent strategies of the businesses active in such sub-sectors frequently include ‘portfolio maximization’56 and ‘portfolio optimization’56 strategies, and the sub-sectors experience the development of what commentators term ‘patent thickets’56, or multiple overlapping granted patent rights.56 A range of policies, regulatory and business strategies have been developed to limit such patent practices.57 In such circumstances, accurate patent landscaping may provide critical information to policy-makers, investors and individual industry participants, underpinning the development of sound policies, business strategies and research commercialisation plans.

The analysis of the top graphene patent owners (patent assignees) and their patent applications, illustrates the broad relevance of graphene to diverse industry sectors, such as automotive, computing and industrial chemicals.58 The uses of patents between and within these industry sectors and over time can vary widely, adding to the navigational challenges that face readers of even the most accurate graphene IP maps.

Understanding and correctly navigating the rapidly growing patent landscape will be crucial to those who seek to secure future value from GRM research. Patents may be particularly important to the realisation of future commercial value, as patents are a form of IP important to the business models and business practices observed in many of the technology sectors in which GRM research is and will be deployed.56

The IP analysis and discussion in section 1.2.2 highlights the disparity between graphene-related scientific production (represented by publications), see Fig. 9, 10, and graphene-related patent applications (associated with technical exploitation), providing additional evidence of the need for a large scale, concentrated action to bring together leading players in academia (who are, broadly, responsible for scientific production) and industrial leaders (who are, broadly, responsible for patent applications).

Fig. 10 Geographical distribution of scientific papers on graphene as of December 2013.

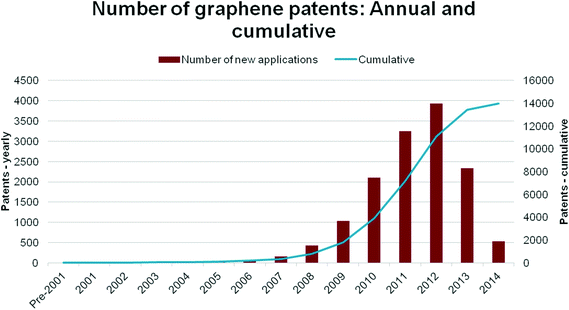

1.2.2. Graphene IP landscape analysis. Fig. 11 indicates that the global IP activity around graphene has surged since 2007, mimicking the trend in research described in section 1.2 and evidence perhaps that research investment worldwide is fuelling rapid growth in graphene technology. Interestingly, IP activity around graphene predates 2004, and patent filings can be found around processes which would have resulted in graphene production from as early as 1896: see, e.g.ref. 59.

Fig. 11 Patent applications on graphene as a function of application year. Note: patents remain unpublished for up to 18 months from their filing. Accordingly, 2013 and 2014 are under-represented. Data updated as of July 2014.

The patent space prior to 2006 is dominated by US research institutions and start ups, with a significant volume of filings starting after 2006. The surge in filings from 2007 has been driven heavily by innovations from South Korean multinationals, especially Samsung, as well as research institutes with Samsung connections.

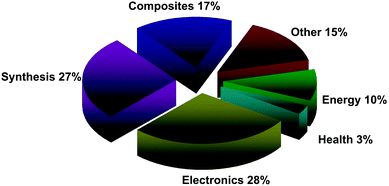

A detailed review of the patent dataset reveals that patents have been filed for a very diverse range of applications including characterization,60 polymer composites,61 transparent displays,62 transistors,63 capacitors,64 solar cells,65 biosensors,66 conductive inks,67–69 windows,70 saturable absorbers,71 photodetectors,72 tennis rackets.73 However, overall, the graphene patent space comprises patent filings in two main sectors: synthesis (e.g. production of graphene by chemical vapour deposition – CVD, exfoliation, etc.,) and electronics (e.g. use of graphene for displays, transistors and computer chips), each ∼30% of the total space, as for Fig. 12, although there is some overlap between sectors. Such overlapping filings can be the result of cross-disciplinary research and can provide evidence of ‘transformational’ and ‘disruptive’ technologies.

Fig. 12 Proportion of overall graphene patents, by sector as of July 2014.

Considering the wide range of potential graphene applications, indicative of crossing vertical technology ‘silos’ (with applications in sectors as diverse as electronics, ICT, energy, consumer goods, polymers, automotive industry, medicine, and industrial chemicals/catalysis), the dominance of synthesis and electronics alone suggests this is an early stage space with plenty of scope for development.

Additionally, given the relatively young age of this space and the demands for mass-production, the strong drive toward synthesis observed in the patent data is unsurprising.74 As the underlying graphene technology space develops and the patent space matures, re-distribution seems inevitable, probably away from synthesis and towards the currently less well-established (or not yet conceived) end-use applications.

Our analysis of filing geography gives an indication of the key innovation locations and potential markets. This interpretation is further supported by noticing that the patenting trend closely follows the standard technology evolution pattern as discussed in ref. 75.

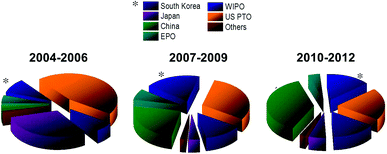

Fig. 13 plots the geographical breakdown of graphene patent filings by filing jurisdiction. Companies tend to file first in their home jurisdiction. The second filing location (other than in the case of an international Patent Cooperation Treaty – PCT – application) is likely to be a key market or a key manufacturing location.

Fig. 13 Graphene patent filing authorities. EPO, European patents office; WIPO, World Intellectual Property Organization; US PTO United States Patent and Trademark Office.

Fig. 13 provides evidence of a relative increase in graphene patent filings in South Korea from 2007 to 2009 compared to 2004–2006. This could indicate increased commercial interest in graphene technology from around 2007. The period 2010 to 2012 shows a marked relative increase in graphene patent filings in China. It should be noted that a general increase in Chinese patent filings across many ST domains in this period is observed.76 Notwithstanding this general increase in Chinese patent activity, there does appear to be increased commercial interest in graphene in China. It is notable that the European Patent Office contribution as a percentage of all graphene patent filings globally falls from a 8% in the period 2007 to 2009 to 4% in the period 2010 to 2012.

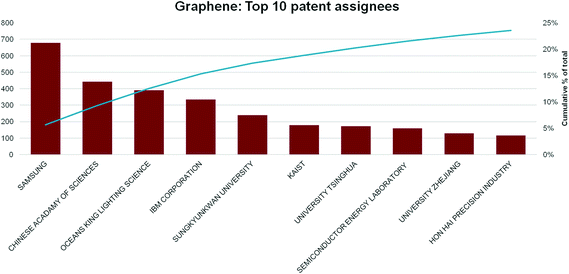

The importance of the US, China and South Korea is emphasised by the top assignees, shown in Fig. 14. The corporation with most graphene patent applications is the Korean multinational Samsung, with over three times as many filings as its nearest rival. It has also patented an unrivalled range of graphene-technology applications, including synthesis procedures,77 transparent display devices,78 composite materials,79 transistors,80 batteries and solar cells.81 Samsung's patent applications indicate a sustained and heavy investment in graphene R&D, as well as collaboration (co-assignment of patents) with a wide range of academic institutions.82,83

Fig. 14 Top 10 graphene patent assignees by number and cumulative over all time as of end-July 2014. Number of patents are indicated in the red histograms referred to the left Y axis, while the cumulative percentage is the blue line, referred to the right Y axis.

It is also interesting to note that patent filings by universities and research institutions make up a significant proportion (∼50%) of total patent filings: the other half comprises contributions from small and medium-sized enterprises (SMEs) and multinationals.

Europe's position is shown in Fig. 10, 12 and 14. While Europe makes a good showing in the geographical distribution of publications, it lags behind in patent applications, with only 7% of patent filings as compared to 30% in the US, 25% in China, and 13% in South Korea (Fig. 13) and only 9% of filings by academic institutions assigned in Europe (Fig. 15).

Fig. 15 Geographical breakdown of academic patent holders as of July 2014.

While Europe is trailing other regions in terms of number of patent filings, it nevertheless has a significant foothold in the patent landscape. Currently, the top European patent holder is Finland's Nokia, primarily around incorporation of graphene into electrical devices, including resonators and electrodes.72,84,85

European Universities also show promise in the graphene patent landscape. We also find evidence of corporate-academic collaborations in Europe, including e.g. co-assignments filed with European research institutions and Germany's AMO GmbH,86 and chemical giant BASF.87,88 Finally, Europe sees significant patent filings from a number of international corporate and university players including Samsung,77 Vorbeck Materials,89 Princeton University,90–92 and Rice University,93–95 perhaps reflecting the quality of the European ST base around graphene, and its importance as a market for graphene technologies.

There are a number of features in the graphene patent landscape which may lead to a risk of patent thickets96 or ‘multiple overlapping granted patents’ existing around aspects of graphene technology systems. There is a relatively high volume of patent activity around graphene, which is an early stage technology space, with applications in patent intensive industry sectors. Often patents claim carbon nano structures other than graphene in graphene patent landscapes, illustrating difficulties around defining ‘graphene’ and mapping the graphene patent landscape. Additionally, the graphene patent nomenclature is not entirely settled. Different patent examiners might grant patents over the same components which the different experts and industry players call by different names. Use of a variety of names for the same components could be a deliberate attempt at obfuscation. There is some support for this view in the relevant academic literature. E.g., ref. 97 suggested that where patent assessment quality is low (e.g. due to inadequate expertise by patent examiners of a particular technology space), leading players might engage in high-volume patenting to deliberately create a ‘patent thicket’, with a range of possible negative effects on innovation.98

Despite the challenges described above, there are a number of important opportunities of which academics, SMEs and multinationals should take advantage, including increased occurrences of academia-industry collaboration (following the lead of South Korea and the US); preparing for the inevitable re-distribution of the graphene patent space as it matures and, most likely, moves away from synthesis, towards the currently less well-established (or not yet conceived) end-use applications.

2. Fundamental research

One of the reasons for the fast progress of graphene research is the wealth of its unique properties. However, what makes it really special, and gives it a disruptive value, is that all those properties are combined in a single material. Transparency–conductivity–elasticity can find use in flexible electronics, high mobility (μ)-ultimate thinness in efficient transistors for RF applications, while transparency–impermeability–conductivity can be exploited for transparent protective coatings. The list of such combinations is ever growing. The most important are probably those not yet explored, as they might lead to new applications.

Currently, several record high characteristics have been achieved with graphene, some of them reaching theoretically predicted limits: room temperature (RT) μ of 2.5 × 105 cm2 V−1 s−1 (ref. 99) and μ ∼ 6 × 106 cm2 V−1 s−1 at 4 K,100 a Young modulus of 1 TPa and intrinsic strength of 130 GPa;18 impermeability for gases101 and so on. Graphene also has record high thermal conductivity κ (∼2000 to 5300 W m−1 K−1 (ref. 102) and can withstand high current densities (million times higher than copper).103

The surge in graphene research also paved the way for experiments on many other 2d crystals.5 One can use similar strategies to graphene to get new materials by mechanical5 and liquid phase exfoliation of LMs38 or CVD. An alternative strategy to create new 2d crystals is to start with existing ones (e.g. graphene) and use them as atomic scaffolding for modification by chemical means (graphane33 or fluorographene34). The resulting pool of 2d crystals is huge, and covers a range of properties: from the most insulating to the best conductors, from the strongest to the softest. Suitable properties may be used depending on the targeted application. E.g., to cover a range of various conductance properties (but keeping the strength) one might use combinations of graphene and fluorographene, the latter being insulating, but almost as strong as the former.

For the long-term future, opportunities can be envisioned, combining conducting graphene with semiconducting and optically active 2d crystals, to create hybrid multilayer superstructures. If 2d crystals hold a wide variety of properties, the sandwiched structures of 2, 3, 4… layers of such materials can further offer longer term prospectives. By assembling 2d structures, one can engineer artificial 3d crystals, displaying tailored properties. Since such 2d based heterostructures104,105 can be assembled with atomic precision and individual layers of very different identity can be combined together, the properties could in principle be tuned to fit any application. Furthermore, the functionality of those stacks is embedded in the design of such heterostructures. First proof of principle devices are already available,106 such as vertical tunnelling transistors106 which show promising electrical characteristics.107,108 Starting with fundamental studies, the aim is to learn how to tune properties of such hetero- or hybrid systems in order to target a specific functionality.

Exploiting the full potential offered by the electronic and mechanical properties of GRMs in applications requires extensive fundamental studies. Graphene transistors and interconnects have an opportunity to complement and extend current Si technology. One route towards the use of graphene transistors for logic devices relies on creating a controllable band gap. The limited on/off current ratio (ION/IOFF) may be resolved in new transistor designs, which exploit the modulation of the work function of graphene,109 or carrier injection from graphene into a fully-gapped semiconductor,110 by gaining control over vertical (rather than planar) transport through various barriers,106 or using graphene as a gate, electrode, or interconnect. For the latter application of graphene, its electrical and thermal conductivities play an important role, so that studies of those properties should be intensified, especially in polycrystalline CVD-material.

Nature offers a very broad class of 2d crystals. There are several LMs which retain their stability in the form of monolayer and whose properties are complementary to those of graphene. Transition metal oxides (TMOs) and transition metal dichalcogenides (TMDs) also have a layered structure.111 Atoms within each layer are held together by covalent bonds, while van der Waals (vdW) interactions hold the layers together.111 LMs include a large number of systems with interesting properties.111E.g., NiTe2 and VSe2 are semi-metals,111 WS2, WSe2, MoS2, MoSe2, MoTe2, TaS2, RhTe2, PdTe2 are semiconductors,111 h-BN, and HfS2 are insulators, NbS2, NbSe2, NbTe2, and TaSe2 are superconductors.111 Moreover, there are other LMs such as Bi2Se3, Bi2Te3 that show thermoelectric properties111 and may behave as topological insulators (TIs).112 Atomic layers of these materials can be produced,5 using mechanical or liquid-phase exfoliation, see section 4 for more details on production.

A wider variety of 2d materials are also being explored, such as the graphene analogue of silicon (i.e., silicene),113,114 germanium (i.e., germanene),115 phosphorus (i.e., phosphorene)116 and tin (i.e., stanene).117,118 Another large LM class is that comprising the MXenes.119,120 These are derived by exfoliating the so called MAX Phases, i.e. layered, hexagonal carbides and nitrides having the general formula: Mn+1AXn, (MAX) where n = 1 to 3, M is an early transition metal, A is an A-group (mostly IIIA and IVA, or groups 13 and 14) element and X is either carbon and/or nitrogen.

Chemical modification of graphene33 allows the creation of another class of 2d crystals with a non-zero bandgap, such as graphane33 and fluorographene.34 Modification of these materials is interesting, e.g. p-doped graphane could be an electron–phonon superconductor121 with a critical temperature (Tc) above 77 K.121

There is also a growing number of graphane analogues, such as germanane,122 and stanane.123Ref. 122 synthesized mm-scale crystals of hydrogen-terminated germanane from the topochemical deintercalation (i.e., selective for a specific chemical element) of CaGe2 resulting in a lattice of Ge atoms with an analogous geometry to the sp3-hybridized graphane surface, in which every Ge atom is terminated with either H or OH above or below the layer.124 Germanane is thermally stable up to 75 °C.122 Above this T, dehydrogenation and amorphization begin to occur.122

2.1. Electronic transport

Graphene's promise to complement or even replace semiconductors in micro- and nanoelectronics is determined by several factors. These include its 2d nature, enabling easy processing and direct control of the charge carriers, fast moving (quasi-relativistic) electronic excitations yielding a high μ (almost equal between electrons and holes) – both at RT and low T, and high κ. Graphene crystals have two well-established allotropes, single layer graphene (SLG), where charge carriers resemble relativistic Dirac particles,125 and bilayer graphene (BLG), where electrons also have some Dirac-like properties, but have a parabolic dispersion.125 However, unlike SLG, where the absence of a gap is protected by the high symmetry of the honeycomb lattice, BLG is more versatile: a transverse electric field can open a gap126–128 and its low-energy band structure can be qualitatively changed by strain.129 Each of these has advantages and disadvantages for a given application, and one has to learn how to control and exploit them to create functional devices.

Concerning μ, further research is needed to understand the effects of defects and charge inhomogeneities, as well as development of doping techniques. The influence of various dielectric substrates or overgrown insulators also needs further basic understanding in order to optimize device performance. Further studies of transport regimes and optoelectronic effects in gapped BLG are needed for FET applications. Considering the possible use of an electrically induced gap in BLGs for quantum dots (QDs) and engineered QDs-based circuits (e.g., for quantum information processing130), a detailed understanding of the influence of disorder and Coulomb interaction on the T dependence of conductivity is required, including the nature of variable range hopping in gapped BLGs, which can be generically described by an exponential increase of resistance following R ∼ exp[(T0/T)p] (ref. 131) with T0 a constant depending on the localization length and density of states, whereas the exponent is given by p = 1/2 for the Efros–Shklovskii mechanism132 and p = 1/3 for the Mott hopping regime;131 the dominating regime depending on the material.133

Besides the studies of sample-average graphene parameters, such as, Rs, it is highly desirable to get insights into local properties of graphene used in devices. This can be achieved by means of several non-destructive techniques: Raman spectroscopy,134–136 Kelvin probe microscopy,137 local compressibility measurements,138 and non-contact conductivity, using capacitive coupling of a probe operated at high frequency.139 The application of such techniques to graphene is natural, due to its 2d nature. These techniques can be used to study GRMs to reveal the role of inhomogeneity in carrier density, the role of particular substrates, and can shed light on the role of structural defects and adsorbents in limiting device performance.

The peculiar properties of electrons in SLG (their similarity to relativistic Dirac particles) make a p–n junction in graphene transparent to electrons arriving at normal incidence.140,141 On one hand, this effect, known as Klein tunneling,141 makes it difficult to achieve a complete pinch-off of electric current, without chemical modification or patterning.142 On the other hand, it offers a unique possibility to create ballistic devices and circuits where electrons experience focusing by one or several p–n interfaces.143 The development of such devices requires techniques of non-invasive gating [see, e.g., ref. 144]. Another method to improve quality of graphene is to suspend it over electrodes (also used as support) and then clean it by current annealing.144,145 This enables one to achieve highly homogeneous carrier density, and micron-long mean free paths, enabling a detailed investigation of electronic properties at very low excitation energies.145

Understanding the transport properties of graphene also includes its behaviour in the presence of a strong – quantising – magnetic field. As a truly 2d electron system, graphene displays the fundamental phenomenon of quantum Hall effect (QHE),146–150 which consists in the precise quantisation of Hall resistance of the device.150 Both integer and several fractional QHE (FQHE) states have been observed,151,146,148 the latter requiring very high crystalline quality and pure material,151 where the Coulomb interactions between electrons can become very strong, leading to the formation of correlated states of matter.152 The QHE robustness in SLG opens a possibility to explore one, up to now, impossible regime of quantum transport in solid-state materials: the interplay between QHE and superconductivity in one hybrid device made of graphene and a superconductor with a high critical magnetic field (e.g., a NbTi alloy153). Moreover, the particular robustness of QHE in graphene on the Si face of SiC154 (still waiting for a complete understanding155) makes it a suitable platform for a new type of resistance standard.154

One of the issues in the fabrication of GFETs is electrostatic gating. Atomic Layer Deposition (ALD) of high- [where is the dielectric constant] dielectrics (Al2O3, HfO2) is one possibility worth further exploration, due its accurate control of layer thickness.156 After such processing, graphene can be transferred to a Si substrate in which deep trenches previously filled with metal (e.g., W) form the back-gate, and the source and drain are subsequently deposited on the graphene itself. Such an approach offers a possibility to build devices with complex architectures. However, ALD uses alternating pulses of water and precursor materials157 and, since graphene is hydrophobic,158 the deposition of a uniform, defect-free dielectric layer is difficult,159 and requires further optimization. Another promising technological advance is offered by photochemical gating.160 There are several polymers where UV light converts Cl atoms into acceptors, whereas thermal annealing returns them into a covalently bound state.161 Due to easy charge transfer between graphene and environment, UV illumination can modulate carrier density in graphene covered by such polymers, enabling non-volatile memory cells.162

For device applications, graphene contacts with metals and semiconductors require further studies: charge transfer between materials, formation of Schottky barriers, and graphene p–n junctions. The contacts play a crucial role for several devices: for superconducting proximity effect transistors,163 where they determine how Cooper pairs penetrate graphene, and for transistors used to develop quantum resistance standard, also needing very low resistance contacts to reduce overheating at the high-current performance of the resistance standard. Chosen to match the work functions of graphite and metals, the most common combinations are Cr/Au,164 Ti/Au164,165, Ti/Pt,166 and Ti/Pd/Au,167 the latter exhibiting lower contact resistances in the 10−6 Ω cm−2 range.167 The best results to date, down to 10−7 Ω cm−2, were obtained for Au/Ti metallization with a 90 s O2 plasma cleaning prior to the metallization, and a post-annealing at ∼460 °C for 15 min.168

2.2. Spectroscopic characterization

Spectroscopy is an extremely powerful non-invasive tool in graphene studies. Optical visibility of graphene, enhanced by an appropriately chosen substrate structure,169–171 makes it possible to find flakes by inspection in an optical microscope. While a trained person can distinguish SLG from FLG by “naked eye” with high fidelity, Raman spectroscopy has become the method of choice for a more systematic analysis.134–136

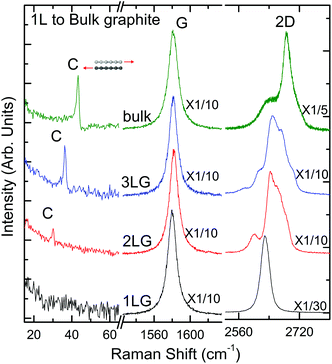

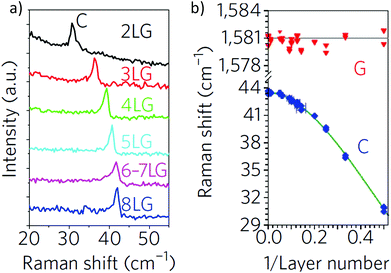

The Raman spectrum of graphite was measured 44 years ago.172 Since then, Raman spectroscopy has become a commonly used characterisation technique in carbon ST, as a method of choice to probe disordered and amorphous carbons, fullerenes, nanotubes, diamonds, carbon chains, and poly-conjugated molecules.173 The Raman spectrum of graphene was first reported in 2006.134 This triggered a huge effort to understand phonons,134,136 electron–phonon,134,136,174 magneto-phonon,175–177 and electron–electron178 interactions, and the influence on the Raman process of number134 and orientation134,136 of layers, electric179–181 or magnetic182,183 fields, strain,129,184 doping,179,185 disorder,136 defects,186 quality187 and types187 of edges, functional groups.188 The graphene electronic structure is captured in its Raman spectrum that evolves with the number of graphene layers (N).134 The 2D peak changes in shape, width, and position for increasing N (see Fig. 16), reflecting the change in the electron bands. The 2D peak is a single band in SLG, whereas it splits in four in BLG.134 Since the 2D shape reflects the electronic structure, twisted multi-layers can have 2D peaks resembling SLG.134 FLGs can also be characterized by the interlayer shear mode189 (see Fig. 17), i.e. the C peak that probes the interlayer coupling.190 This peak scales from ∼44 cm−1 in bulk graphite to ∼31 cm−1 in BLG (see Fig. 17).190 Layer breathing modes (LBMs) can also be observed in the Raman spectra of FLGs, via their resonant overtones in the range 80–300 cm−1.191 They can also be addresses through the stokes and anti-stokes combinations with the D' peak,134,196 or in twisted samples.2335

Fig. 16 Raman spectra of SLG (1LG), BLG (2LG), TLG (3LG), and bulk graphite measured at 633 nm. Adapted from ref. 204.

Fig. 17 (a) C peak as a function of number of layers. (b) Fitted C- and G-peak position as a function of inverse number of layers. Adapted from ref. 134.

It is important to note that, although being an in-plane mode, the 2D peak is sensitive to N because the resonant Raman mechanism that gives rise to it is closely linked to the details of the electronic band structure,135,136 the latter changing with N, and the layers relative orientation.192 On the other hand, the C peak and LBMs are a direct probe of N,190,191,193–196 as the vibrations themselves are out of plane, thus directly sensitive to N. Raman spectroscopy has provided key insights in the related properties of all sp2 carbon allotropes, graphene being their fundamental building block, and other carbon-based materials, such as amorphous, nanostructured and diamond-like carbons173,188,197–203 Raman spectroscopy has also huge potential for LMs,204,205 other than graphene, see section 2.8.1.

Studies of the magneto-phonon resonances206,207 enable to directly measure the electron–phonon coupling in SLG, BLG, and multilayers.177,206–208,209–211 Optical spectroscopy allows to study the split-bands in BLG,212,213 and the analysis of disorder-induced phonon-related Raman peaks134 provides information on sample quality complementary to that extracted from transport measurements.

Angle-resolved photoemission spectroscopy (ARPES) directly probes band dispersions and lattice composition of electron states, which determine the pseudospin symmetry of electronic states.214,215

Further improvement of the above-mentioned optical characterisation techniques and development of new approaches are critically important for in situ monitoring. Outside the visible-range and Infra-Red (IR) optical spectroscopy, detailed studies of defects in graphene can be addressed using scanning transmission electron microscopy (STEM), energy loss spectroscopy, low-angle X-ray spectroscopy, and resonant inelastic X-ray scattering (RIXS). The development of a standardised optical characterisation toolkit with the capability to monitor N, as well as quality and doping level, is one of the key needs for the progress in graphene mass manufacturing. Since there are several routes towards viable mass production, described in section 4, the suitable energy/wavelength range for the standardised spectroscopic characterisation toolkit is not known yet, thus spectroscopic studies of graphene need to be carried out over a broad energy range, from microwaves and far IR to UV and X-ray.

Scanning tunnelling microscopy (STM) is another important tool. Since electronic states in graphene can be directly addressed by a metallic tip,216 STM studies may be instrumental for understanding the morphology and electronic structure of defects: vacancies, grain boundaries (GBs), functionalised faults, and strongly deformed regions (‘bubbles’) resulting from processing or transfer. Such studies will be necessary for materials manufactured using each of the methods discussed in section 4, and to investigate the result of subjecting graphene to various gases. The use of STM under extreme conditions, such as strong magnetic fields, can probe local properties of electrons in Landau levels, and their structure close to defects.

2.3. Magnetism and spin transport

The control and manipulation of spins in graphene may lead to a number of novel applications and to the design of new devices, such as spin-based memories217 or spin logic chips.218 Graphene is uniquely suitable for such applications, since it does not show sizeable spin–orbit coupling,74 and is almost free of nuclear magnetic moments.219 Graphene currently holds the record for the longest spin relaxation length at RT, initially evaluated to be ∼5 μm,219 with promise for applications.220–222 At lower T, there are indications that the spin relaxation length could approach ∼100 μm.223 Further studies require the investigation of spin injection, diffusion, relaxation and of the interfaces between graphene and magnetic materials.

The magnetic properties of graphene are connected to the defects. As a 2d electronic system, graphene is intrinsically diamagnetic.224 However, defects in graphene, as well as localisation of electrons in or around defects (vacancies, edges and covalently bonded dopants) can generate localised magnetic moments which directly modulate the spin current, as it has been proven in the cases of hydrogen adatoms and lattice vacancies.225,226

Edge magnetism has been predicted in graphene nanoribbons (GNRs) for certain edge geometries;227 the structure of graphene nanomesh, obtained by using block-copolymer nanopatterning of graphene, was also theoretically shown to yield RT magnetic states affecting spin transport.228

An enhanced paramagnetic signal was measured in graphene crystallites,229 and it was found that magnetism is enhanced in irradiated samples,229 similar to graphite.230 Strong enhancement of paramagnetism was also observed in fluorographene.231

An unambiguous assessment of the nature and the formation of magnetic moments in graphene and in FLG, and the resulting control of their properties would be a major advance and would significantly expand graphene applications.

The necessary steps towards a full portrait of graphene's magnetic properties are a complete understanding of disorder as well as (quantum) confinement (as for graphene quantum dots, GQDs, and GNRs) on spin relaxation and dephasing. This requires the investigation of the limits of conventional spin relaxation mechanisms common to metals and small gap semiconductors, i.e. Elliot–Yafet (EY)232,233 and Dyakonov–Perel234 (DP). EY was originally232,233 derived for spin relaxation in metals, and relates the spin dynamics with electron scattering off impurities or phonons.232,233 Each scattering event changes the momentum, with a finite spin-flip probability, that can be derived by perturbation theory (assuming weak spin–orbit scattering). This gives rise to a typical scaling behaviour of the spin relaxation time proportional to the momentum scattering time. DP234 is an efficient mechanism of spin relaxation due to spin orbit coupling in systems lacking inversion symmetry.234 Electron spins precess along a magnetic field which depends on the momentum.234 At each scattering event, the direction and frequency of the precession change randomly. The scaling behaviour is opposite to EY, with a spin relaxation time which is inversely proportional to the momentum scattering time.235

Two other mechanisms of spin relaxation in graphene have been proposed.236,237 One involves local magnetic moments which produce resonances and fast spin relaxation based on the resonant scattering of electrons off magnetic moments, which can be due to nonmagnetic adatoms, organic molecules, or vacancies.236 The other is related to the interplay between spin and pseudospin quantum degrees of freedom when disorder does not mix valleys.237 Such strong contribution of spin/pseudospin entanglement is particularly important when defects or impurities at the origin of local Rashba spin–orbit coupling (i.e. a momentum-dependent splitting of spin bands in 2d systems)238 preserve the pseudospin symmetry and lead to very long mean free path.

The role of edges on spin scattering and relaxation has yet to be clarified, as well as the case when the injected spin-polarized charges flow in close proximity (and interact) with other extrinsic spins (in localized or more extended charged states, located below or on top of the graphene).

The role of the substrate, contacts and environmental conditions on spin relaxation needs to be clarified. A detailed comparison between exfoliated graphene on SiO2, graphene on BN, and graphene grown on SiC is still missing. This would allow the classification of materials and devices' parameters, which have, to date, shown limited spin transport. These results could be compared with spin transport and relaxation in suspended graphene devices, which would provide the reference clean system. This is of fundamental importance for further exploration of more complex uses of the spin degree of freedom inside technology.

A systematic comparison of spintronic systems based on SLG, BLG and FLG still needs to be carried out. With a focus on spin ensembles, the RT capability of graphene devices has to be ascertained.

The knowledge derived from these investigations could be exploited in multiple ways. E.g., novel studies could be carried out to induce (para-) magnetism by introducing localised defect states in a controlled way, or by decoration of the surface with magnetic atoms or molecules. In the search for fingerprints of local magnetic ordering states and magnetoresistance profiles, chemically modified graphene (CMG)-based materials should be produced to investigate the potential of new physical phenomena. Other topics include studying electronic transport in graphene in proximity of ferromagnetic materials or ferromagnetic insulators (magnetic oxides as EuO, EuS, high-Curie T (above which the magnetic state of the system is lost) Yttrium Iron Garnet (YIG), NiO, CoFe2O4). This may induce spin polarization, which could be exploited to demonstrate spin filtering effects.239 Related issues focus on the existence of nanomagnetism of magnetic materials deposited on graphene, and the understanding of the interfacial electronic structure of such contacts.

2.4. Polycrystalline graphene

The GB role in transport and optical properties240 needs to be fully investigated, especially in view of large-scale production. The theoretical exploration of the properties of large size realistic models is crucial for guiding experiments.

Microscopic studies of grain boundaries are needed to determine their precise lattice structure and morphology, as well as the related functionalization of broken carbon bonds by atoms/molecules acquired from environment. Grain boundaries in the 2d graphene lattice are topological line-defects consisting of non-hexagonal carbon rings, as evidenced by aberration corrected high resolution TEM investigations.241 Although they are expected to substantially alter the electronic properties of the unperturbed graphene lattice,242 so far little experimental insight into the underlying mechanisms is available. GB introduce tension in graphene nanocrystals,243 which, in turn, bears influence on the electronic properties, including local doping. From the point of view of electronic transport, GB generate scattering, possibly with a strongly nonlinear behaviour, but present knowledge on the precise effects is incomplete. Ref. 244 suggested a scaling behaviour of polycrystalline graphene,244 which gives μ ∼ 300000 cm2 V−1 s−1 at RT for an average grain size of 1 μm and clean GB. This also shows the need for a more detailed GB chemical characterization, since these are more chemically reactive and could drive an essential part of the resistance of the material. Indeed, e.g., CVD grown samples fall behind by about an order of magnitude compared to mechanically exfoliated ones.9 The internal GB structure, and the resulting broken electron-hole (e–h) and inversion symmetry may generate thermo-power245 and local rectification,246 which may affect high current performance. Depending on their structure, GBs have been initially theoretically predicted to be highly transparent,247 or perfectly reflective,247 while other studies suggest GB act as molecular metallic wires248 or filter propagating carriers based on valley-index.249

A comprehensive picture of GBs’ spectral properties is thus missing, and should be established using STM and atomic force microscopy (AFM), and local optical probes,250 given possible specific light absorption and emission,251,252 The use of graphene for energy applications, in solar cells, also requires understanding of the GB role in the charge transfer between graphene and environment. Moreover, optics, combined with electrochemistry, is needed to figure out ways to re-crystallize graphene poly-crystals, and to assess durability (i.e. until when the (opto)electronic and thermal properties are maintained without degradation). There is growing evidence that GBs degrade the electronic performance.253,254

2.5. Thermal and mechanical properties of graphene

Practical implementation of graphene requires the understanding of its performance in real devices, as well as its durability under ambient and extreme conditions. A specialised effort will be needed to study the reliability of graphene-based devices, such as electric or thermal stress tests, device lifetime, etc. To preserve performance, it is likely that some protection of the graphene and the metals will be needed to minimize environmental effects.

Due to the sp2 hybridization, pristine SLG is very strong, and it takes 48000 kN m kg−1 of specific strength (i.e. strength (force per unit area at failure) divided by density) before breaking18 (compare this to steel's 154 kN m kg−1 (ref. 255)). This makes graphene a desirable addition to lightweight polymers, and the enforcer of their mechanical properties. Moreover, as ultrathin stretchable membrane, SLG is an ideal material for nonlinear tuneable electromechanical systems. However, for the practical implementation of realistic graphene systems, a detailed study of mechanical properties of polycrystalline graphene is needed in vacuum, ambient environment, and of graphene embedded in polymers. Studies of mechanical properties of GBs between graphene nano-crystals will require a further improvement of scanning techniques. The durability of graphene in various systems will also depend on its ability to recrystallize upon interaction with various chemical agents, as well under various types of radiation, from UV and soft X-rays to cosmic rays.

The application of graphene in the electronics and optoelectronics requires detailed understanding of its thermal and mechanical properties. Several early experiments,256,257 indicate that graphene is a very good heat conductor, due to the high speed of acoustic phonons in its tight and lightweight lattice. Detailed studies of heat transfer through graphene and the interfacial Kapitza thermal resistance258 (i.e. the measure of an interface's resistance to thermal flow) between graphene and other materials (metallic contacts, insulating substrates, polymer matrix) are needed. Graphene performance at high current may lead to overheating, and quantitative studies (both experimental and theoretical) are needed to compare its performance with the standards set in electronics industry. Moreover, overheating upon current annealing may lead to its destruction, so that studies of thermal and thermo-mechanical properties are needed to assess its durability in devices, and optimise its use in realistic and extreme conditions. In particular, in situ studies of kinetics and dynamics at the break point (use of HRTEM would be appropriate) are a challenging but necessary step towards practical implementation.

Experimental studies need to be complemented by ab initio and multiscale modelling of nanomechanical and heat transport properties, and modelling of graphene at strong non-equilibrium conditions (see Section 2.10.4).

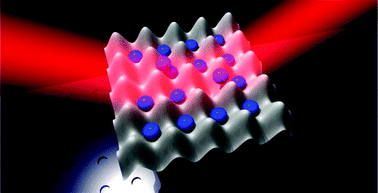

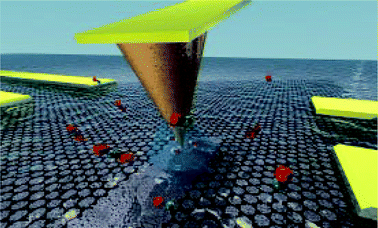

2.6. Artificial graphene structures in condensed-matter systems

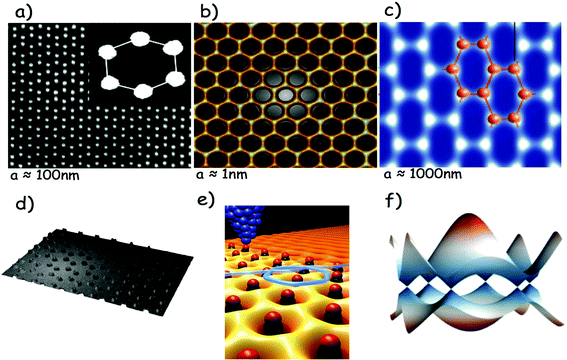

Advances in the design and fabrication of artificial honeycomb lattices or artificial graphene (AG) pave the way for the realization, investigation, and manipulation of a wide class of systems displaying massless Dirac quasiparticles, topological phases, and strong correlations. Such artificial structures are currently created by three approaches: atom-by-atom assembling by scanning probe methods,259 nanopatterning of ultra-high- μ two-dimensional electron gases (2DEGs) in semiconductors,260 and optical trapping of ultracold atoms in crystals of light.261 Examples of AG structures realized so far are shown in Fig. 18. The interplay between single-particle band-structure-engineering,262 cooperative effects and disorder263 can lead to interesting manifestations in tunnelling264 and optical spectroscopies.262

Fig. 18 (a) SEM image of AG structure realized by e-beam lithography and reactive ion etching on a GaAs/AlGaAs heterostructure. Electrons localize underneath the nanopillars (white dots; also shown in (d).260 (b) STM topography of a molecular graphene lattice composed of 149 carbon monoxide molecules.259 (c) A honeycomb optical lattice for ultracold K atoms.261 (e) Electron moving under the prescription of the relativistic Dirac equation. The light blue line shows a quasi-classical path of one such electron as it enters the AG lattice made of carbon monoxide molecules (black/red atoms) positioned individually by an STM tip (comprised of Ir atoms, dark blue). (f) Tight-binding calculations of the Dirac Fermion miniband structure of the AGs in (a) and (d).

One of the reasons for pursuing the study of AGs is that these systems offer the opportunity to reach regimes difficult to achieve in graphene, such as high magnetic fluxes, tuneable lattice constants, and precise manipulation of defects, edges, and strain. These can enable tests of several predictions for massless Dirac fermions,265,266 Studies of electrons confined in artificial semiconductor lattices, as well as studies of cold fermions and bosons in optical lattices, may provide a key perspective on strong correlation and the role of disorder in condensed matter science. AG systems might open new avenues of research on spin–orbit coupling, with impact on spintronics, and frontier issues related to novel topological phases.

These are centred on TIs,267–269 that have emerged as a promising class of materials in this regard.269 Strong spin–orbit coupling results in an insulating bulk and metallic edge or surface states (respectively for 2d and 3d systems). These states are “topological” in the sense that they are insensitive to smooth changes in material parameters, and also exhibit unique spin textures. One remarkable phenomenon is the Quantum Spin Hall Effect (QSHE), which for a 2d TI, consists of pairs of edge counter-propagating modes with opposite spins.112 Meanwhile, the surface state of a 3d TI exhibits spin-momentum locking, where the spin is perpendicular to the electron momentum. The spin texture of these states implies that backscattering by non-magnetic impurities is strongly suppressed, resulting in insensitivity to disorder and long coherence times. Due to this behaviour, TIs are promising for next-generation electronics, as well as for spintronics and quantum computing.270 The QSHE effect was first predicted in graphene,112 linked to the honeycomb topology of the lattice112 and to the contribution of a weak spin–orbit coupling.112 AG structures in systems properly engineered to display large spin–orbit coupling represent viable candidates to simulate TI states. There are further possibilities for research arising from the demonstration that single atoms can function as atomic-size gates of a 2d electron system at noble metal surfaces, whereby simple molecules, such as CO, function as repulsive potentials for surface electrons when shaped into open and closed quantum structures. Individual CO molecules arranged on Cu(111) were used as a tuneable gate array to transform a 2d gas of electrons moving through these lattices (Fig. 18).201

Control over every lattice position and potential would result in control of the spatial texture of the hopping parameter, ultimately allowing observation of electronic ordering into ground states, rarely encountered in natural systems. In AGs, molecular graphene, artificial lattices in semiconductors, and optical lattices of cold atoms, controlled densities of ‘artificial impurities’ can be introduced259 in otherwise perfect lattices. Studies of these artificial structures may provide insights on localization and μ degradation in graphene.

2.6.1. Honeycomb lattices in semiconductors. The goal is the creation of nanostructures on a 2DEG confined in high-μ semiconductor heterostructures, creating an in-plane potential with honeycomb geometry so that the miniband structure has well-defined (isolated) Dirac points. The lattice constant in graphene is fixed at ∼1.42 Å. In contrast, AG structures in semiconductors can have tuneable lattice period in the range 10–100 nm,260 so that it should be possible to change interaction regimes from one in which Mott–Hubbard physics (such as the Mott–Hubbard excitation gap and collection spin density modes271) manifests for weak inter-site interactions compared to π–π coupling,260 to one where inter-site interactions drive the creation of novel phases, and to the TI regime in materials with large spin–orbit interaction.

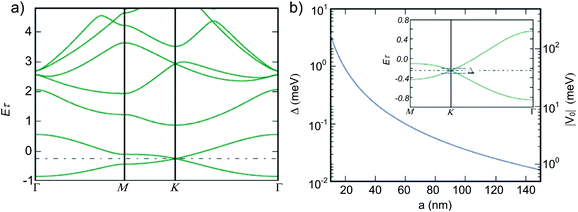

Semiconductor AG may also challenge current thinking in ICT, revealing new physics and applications of scalable quantum simulators for ICT based on semiconductor materials already used in real-life electronic and optoelectronic devices. Due to the embryonic nature of the field, any future activity will be high-risk, but has great potential for discoveries. In semiconductor materials the efforts should be directed to the realization of artificial lattices with small lattice constants and with tuneable amplitude, V0, of the potential modulation. The idea is that the energy range, Δ, in which the bands are linearly dispersing in AGs depends on the hopping energy, therefore this quantity is expected to exponentially increase as we reduce the lattice constant and/or decrease the amplitude of the potential modulation. One target could be the realization of AGs in the regime in which Δ approaches 1 meV. This requires lattice constants ∼20–40 nm (see Fig. 19).

Fig. 19 (a) AG Minibands (energy is in meV) with a lattice period a = 60 nm, r0 = 0.2a (r0 is the width of the potential well) and V0 = 5 meV. A dash-dotted line is drawn at the Dirac-point energy. (b) Energy width, Δ, of the linear part of the spectrum near the Dirac point as a function of a. V0 is varied correspondingly (see the right vertical axis) in order to obtain an isolated Dirac point, i.e. without any other state inside the bulk BZ at the Dirac-point energy. Inset: magnification of the energy bands in panel (a) around the Dirac point energy. The blue dashed lines mark the energy limits of the linear dispersion approximation. Adapted from ref. 260.

One ambitious goal is to observe the dispersive intrasubband plasmon mode of the AG lattice by resonant inelastic light scattering or far-IR spectroscopy. Peculiar to plasmon modes in graphene, in fact, is the specific dependence of energy on electron density: ωplasmon(q) ∝ n1/4q1/2, where q is the in-plane wavevector.272 The difference with the classical square-root dependence n1/2q1/2 of 2d parabolic-band systems is a consequence of the ‘relativistic’ linear dispersion of Dirac fermions,273,274 The manifestations of Dirac fermions are particularly striking under the application of a perpendicular magnetic field.275 In AGs with lattice constant much smaller than the magnetic length (a ≪ lB = ħc/eB) this is expected to lead to graphene-like Landau levels.

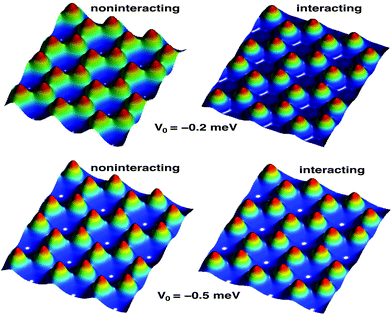

Such peculiar energy level structure, and the resulting anomalies in QHE experiments,145,146,148 have been largely explored in graphene276 where the lattice constant is a = 0.14 nm (lB ≈ 25 nm at 1 Tesla). Tight-binding calculations show that the Dirac Fermion physics occurs when lB/a > 1.275 In AGs with a ∼ 10–20 nm, a Dirac-Fermion Landau level structure is expected for magnetic fields of several Tesla. In molecular AG structures with a ∼ 1 nm, Dirac Fermion physics should emerge at much smaller magnetic fields. The occurrence of such phenomena can be investigated by conventional QHE and by optical spectroscopy. For lB/a < 1, commensurability effects, such as the Hofstadter butterfly,277–279i.e. a fragmentation of the Landau levels structure, begin to emerge and compete with the Dirac-Fermion physics of the honeycomb lattice.280 These effects prevail when lB ≪ a. The impact of the Hofstadter physics on the energy spectrum of a 2DEG in semiconductor heterostructures was studied in magneto-transport in a lateral superlattice of anti-dots arranged in a square geometry.280 Moiré superlattices arising in SLG and BLG coupled to h-BN provide a periodic modulation with length scales ∼10 nm enabling experimental access to the fractal Hofstadter butterfly spectrum.278,279,281 If met, these demanding limits will enable the occurrence of the physics linked to artificial massless Dirac fermions at T above liquid He. Finally, the impact of e–e interaction can be studied theoretically by exploiting advanced methods such as density-functional theory (DFT) and developing a Kohn–Sham DFT coded for 2d electrons moving in a model periodic potential (see Fig. 20)282 and experimentally by optical, transport and scanning probe methods. Additionally artificial topological order and spin-split counter-propagating edge channels can be pursued by creating honeycomb lattices in 2DEGs confined in InSb and InAs heterostructures, with a large spin–orbit coupling. In this area, the long-term vision is the establishment of a new field of quantum information processing and scalable quantum simulations based on nanofabricated AGs in high-μ semiconductor heterostructures.

Fig. 20 Spatial distribution of electrons in AG (with one electron per pillar) calculated for two values of the potential well representing the pillar. The left and right panels show the results without and with e–e interactions.282

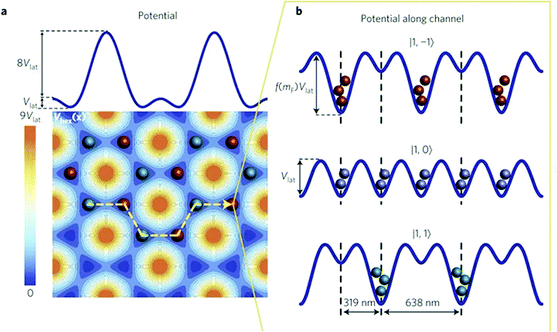

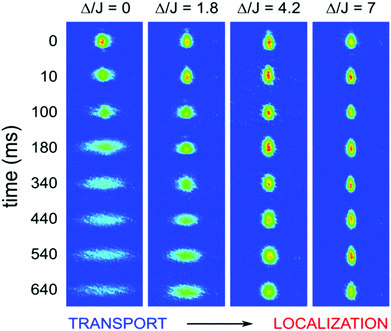

2.6.2. Honeycomb lattices with cold atoms. A different system for the experimental realization of artificial graphene is represented by ultracold atoms in optical lattices.283 Here, the role of electrons is taken by the atoms, which move in the periodic optical potential generated by the interference of different laser beams. The optical realisation of lattice potentials is an intrinsically clean method that allows for the production of disorder-free lattices with well-controlled topology, lattice spacing and potential strength. A suitable arrangement of laser beams can be used to produce honeycomb lattices allowing the simulation of AG. Hexagonal spin-dependent optical lattices, which can be seen as a triangular lattice with a bi-atomic basis where atoms occupy π+ and π− polarized states (Fig. 21), were demonstrated with ultracold bosonic 87Rb in different internal states.284

Fig. 21 (a) Lattice potential with alternating π+ (green spheres) and π− (red spheres) polarization. The upper plot shows a cut through the 2d potential. (b) 1d potential along the channel of the orange dashed line in (a) for particles in different Zeeman states.284

A system of spin-polarised fermionic 40K atoms in honeycomb optical lattices was realized in ref. 261, where the presence of Dirac points in the energy spectrum was measured by momentum-resolved detection of the energy gap between bands. A controlled deformation of the hexagonal lattice was used to control the Dirac cones, moving them inside the Brillouin zone (BZ) and eventually merging them.